A team of scientists at the Cambridge-based Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) announces the discovery of a gene that is responsible for giving bacteria the ability to survive in extremely dangerous environments.

The finding explains why the waters in the Gulf of Mexico, heavily polluted with methane following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, suddenly became full of hydrocarbon-eating bacteria where none was to be found before.

Surveys conducted before the spill occurred found only trace amounts of such microorganisms. Yet, studies conducted shortly after the event began showed massive amounts of the organisms consuming the large amounts of methane released from the ruptured wellhead.

While studying these bacteria, researchers at MIT were able to identify the gene that enabled them to survive and thrive in such a hostile environment. Near the spot where Deepwater Horizon sank, the waters were almost completely devoid of oxygen.

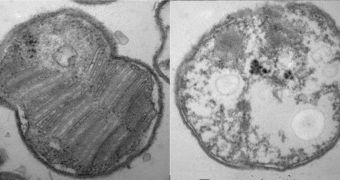

The gene the team found controls the production of a protein called HpnR, whose role is to trigger the production of 3-methylhopanoids. These are essential lipids for the bacteria, since they enable the microorganisms to endure for as long as it takes, until environmental conditions are appropriate again.

Interestingly, this discovery opens the way to new geological studies. By analyzing HpnR concentrations in samples collected from the fossil record, it may become possible for scientists to determine when sudden drops or increases in local oxygen levels occurred in the past.

Details of the study appear in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“The thing that interests us is that this could be a window into the geologic past. In the geologic record, many millions of years ago, we see a number of mass extinction events where there is also evidence of oxygen depletion in the ocean,” postdoctoral researcher Paula Welander says.

“It’s at these key events, and immediately afterward, where we also see increases in all these biomarkers as well as indicators of climate disturbance. It seems to be part of a syndrome of warming, ocean deoxygenation and biotic extinction. The ultimate causes are unknown,” she adds.

Welander, who is based at the MIT Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS), was the leader of the new investigation, together with EAPS professor Roger Summons.

Funds for the research were provided by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) and NASA.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //