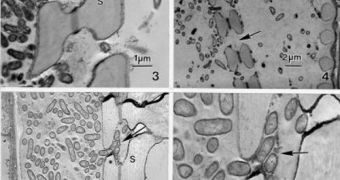

A group of investigators has recently managed to produce never-before-seen images of a bacterial agent in the process of breaking down the cellular walls in grape plants. The new photographs were collected via a technique known as electron microscopy, and the group behind the accomplishment is convinced that these new data will in the future help researchers develop new chemicals that would avert such infections, but without damage to the actual plant. Details of the effort will be published in an upcoming issue of the respected scientific journal Botany, the team adds.

“Basically, we've been interested in determining how the bacteria moves. How do they go from one part of the plant to another?” says College Station-based Texas AgriLife Research plant physiologist Dr B. Greg Cobb, who was a member of the study team. The investigators explains that this dreadful bacteria, which is known to cause Pierce's Disease, affects grape plants stretching all the way from Texas to California. As such, it represents a huge factor in determining the quality and amount of wine produced by distilleries in the United States. The thing about the Disease is that it has no known cure at this point, which is precisely why this study was set up.

The bacteria is known to be “injected” directly into the grape plant by an insect known as the glassy-winged sharpshooter. Once the microorganism Xylella fastidiosa is on the inside, it will immediately proceed to colonize the host plant entirely, until it eventually drains out all of its energy, and the grape plant dies off. “It can be a matter of a few years or more quickly, but plants tend to stop producing before they die, so growers will pull them out of a vineyard,” Cobb explains. He adds that the pathogen was made visible only after the team focused the microscope at a resolution of 100,000th of a millimeter along the pit membrane.

“Then we isolated that very small part at the pit membrane and down the stem or petiole and looked at the xylem there. To basically see the breakdown of the pit membranes had not been seen before,” the expert adds. This investigation was only made possible through grant money obtained from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. The researchers are currently focusing their efforts on developing new methods of preventing the bacteria from completely taking a hold of the plant. This could ensure the creation of a chemical that would stave off the infection before it gets out of hand.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //