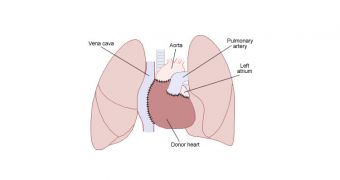

The first few weeks after patients receive a heart transplant are essential to their survival. The risk of rejection is highest during this interval, especially for children, who are weaker overall. A newly-developed imaging technique can now search for signs of rejection without the need for surgery.

Finally having access to a non-invasive imaging technique specialized for transplant health studies is a godsend for doctors. Up until now, they could only gage the evolution of the new organ based on indirect signs, or by performing additional surgery.

Additionally, the approach is able to reveal even the earliest signs of rejection. This gives doctors more time to act, and change their therapeutic approach accordingly, while children will have a higher chance of survival following this type of surgery.

The imaging technique was developed by cardiologists at the Washington University in St. Louis (WUSL) School of Medicine (WUSM). They say that enduring a transplant is hard enough as it is – considering the necessity for administering immunosuppressive drugs – without additional surgeries.

If the method is employed at a large scale, transplant patients will no longer have to undergo invasive imaging testing once every year. Details of how the technique works appear in the latest online issue of the esteemed Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation.

“Many of these children have undergone so many operations, we have lost access to their big blood vessels. Sometimes it’s impossible to do catheterization procedures on them,” explains WUSM professor of pediatrics Charles E. Canter, MD.

The new imaging method that can now be used combines standard Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with the common contrast agent called gadolinium. The chemical marker is not radioactive, and has no negative side-effects on the human body.

Once inside the body, the agent attaches itself to inflamed or damaged portions of arteries and heart muscles, making them appear brighter on MRI scans. The technique was pioneered by senior study author Samuel A. Wickline, MD, a professor of medicine at the university.

“The brighter it is, the more it is associated with coronary artery disease,” Canter explains. The research team also included Doris Duke Clinical Research Fellow, Mohammad H. Madani.

“The results of this pilot study were very promising. But we need to look at more patients,” Canter explains. The researchers had access to data on 29 children who had undergone transplant.

“We’re in the process of developing a bigger study to confirm and refine the results. I think eventually this could be used as a screening technique, not so much to eliminate, but to reduce the number of angiograms,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //