A group of investigators with the University of Würzburg in Germany, led by cancer researcher Almut Schulze, announced at a recent conference that it may be possible to use the gluttonous nature of cancer cells to kill them off. This has been attempted for years, but thus far to no avail. In a new study, Schulze and his group were finally able to use a genetically-targeted drug to destroy tumor cells.

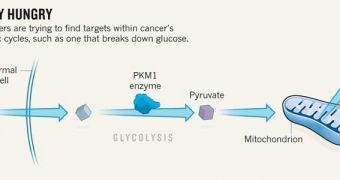

Cancer cells are referred to as gluttonous because they need a lot of resources to produce the vast amounts of energy and molecular building blocks they require to replicate and grow tumors. In order to obtain these resources, signals are released from cells that harness a series of unusual metabolic pathways, reconverting them to feed the cancer.

Scientists first learned about this need many years ago and have been trying to take advantage of it every since. However, all of their efforts have ended in failure, or only partial success. At the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), held this week in San Diego, California, the German group presented a series of very encouraging results.

“The field is at a turning point,” the German researcher told attendants at the conference. For many years at the beginning of the 20th century, cancer was considered to be a metabolic disease, a point of view stemming from the research of German biochemist Otto Warburg. The main argument was that tumor cells appear to have an unusually high appetite for consuming glucose, Nature News reports.

The new investigation basically sends cancer research back to its roots, forcing researchers to come up with new ways of looking at the disease. Tumors need glucose because they can break it down inside cellular organelles called mitochondria to produce the main energy currency of all living things, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), as well as lipids and amino-acids (all essential for building new cells).

The new study is based on two drug targets revealed in a 2009 study conducted by experts with Cambridge-based Agios Pharmaceuticals. The team at the time found that mutations in the genes IDH1 and IDH2 could be associated with a higher incidence of brain and blood cancers. Both genes encode for enzymes that act on the citric acid cycle, an important metabolic pathway for energy production.

On April 6, the Agio team released a new paper reporting the first results from a small clinical trial involving the drug AG-221. This compound inhibits the mutant version of IDH2 and was administered to extremely sick leukemia patients. Of the 10 participants, three dropped out due to infections caused by their cancer, but six of the remaining seven reacted to the therapy.

The team revealed that cancerous cells were subsequently eradicated in five of these six patients. “This is very impressive,” commented the director of hematology with the Wexner Medical Center at the Ohio State University, John Byrd, speaking about these encouraging results. All patients who reacted to the drug were dying, having already undergone numerous other therapies unsuccessfully.

Agios CEO David Schenkein urged caution, saying that experts should first wait and see how long AG-221's effects will last before continuing this line of research. The patients in the clinical trials all received the drug for a maximum of five months, and their cancers were unable to adapt to the attack. However, cancer is unfortunately renowned for its ability to quickly adapt to the latest drugs.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //