A detailed study has recently shown that past global warming events were tremendously harsh to slow-moving critters, as in species ranging from frogs to bats. All species that were unable to move from one climate zone to another fast enough were decimate.

From this point of view, each global warming event in Earth's history can be considered a small-scale extinction event, affecting slow animals and plants most of all. What this research suggests is that species living today should be given room to move freely so that they can adapt to higher temperatures.

A large part of the study was focused on analyzing the Last Glacial Maximum, which occurred about 21,000 years ago. At the time, glaciers moved in from the north, covering Canada and the vast majority of what are now the United States, plus the entire European continent.

As time passed, the world began to warm up again, and glaciers started retreating. A vast number of species was then faced with a choice – either move uphill or follow the glaciers as they retreated, or simply die. Species that could not move fast enough were forced to select the latter option.

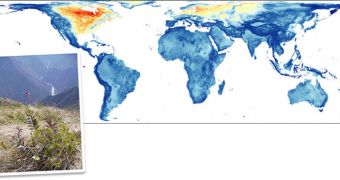

The term used to refer to the speed at which temperatures and habitats were changing is now called climate velocity. It is a measure that is also used to explain that speed at which cold-loving species moved from past habitats to new ones, in order to avoid extinction.

This term was first published in the top scientific journal Nature in 2009, and was coauthored by the Stanford University Carnegie Institution for Science biogeographer Scott Loarie. He says that species facing global warming today will have to make similar choices to their ancient counterparts'.

The new investigation was conducted by ecoinformatics expert Brody Sandel, who is based at the Aarhus University in Denmark, ScienceNow reports. Details of the work were published in the October 6 online issue of the top journal Science.

He explains that the study highlights a genuine danger for species who are unable to move fast enough to avoid a warming weather, or who are prevented from doing so by other factors. Human habitation and land use is such a factor.

If endangered species are not allowed to roam freely so that they can escape higher temperatures, then they are very likely to go extinct. Some of them will survive, if they manage to adapt their bodies fast enough, or introduce new mutations into the gene pool.

However, those are likely to be isolated occurrences, rather than the norm, the investigators conclude.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //