Individuals who lost their sense of smell due to conditions such as trauma and old age could soon have access to a new type of therapy, which will make use of genetic triggers to force the nose to renew its smell sensors. The technique is detailed in the December 8 issue of the scientific journal Neuron.

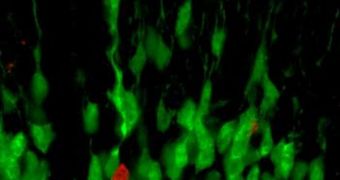

Investigators at the University of California in Berkeley (UCB) say that the nose retains olfactory stem cells for decades. Neuroscientists with the team say that genes can send certain signals to these stem cells, making them develop into an adult stage, replacing damaged cells.

Gary K. Beauchamp, who was not involved in the study, says that the technique has already shown great promise for regenerating damage produced by injuries and a number of diseases. However, there are instances of smell loss that cannot be addressed via this method.

Beauchamp holds an appointment as the director of the Monell Chemical Senses Center, in Philadelphia. “This new paper […] presents an elegant analysis of some of the underlying genetic mechanisms regulating this regeneration,” he says.

“It also provides important insights that should eventually allow clinicians to enhance regeneration, induce it in cases where, for currently unknown reasons, olfactory loss appears permanent, or even prevent functional loss as a person ages,” the expert believes.

The most interesting implication the new study carries is that stem cells belonging to other sense may be used in similar manners, addressing hearing or vision loss. If that turns out to be the case, then researchers really hit the jackpot with this investigation.

“Anosmia – the absence of smell – is a vastly underappreciated public health problem in our aging population. Many people lose the will to eat, which can lead to malnutrition, because the ability to taste depends on our sense of smell, which often declines with age,” John Ngai explains.

Ngai was the lead researcher on the study. He is the Coates Family professor of neuroscience at the UCB Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, and director of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute and the QB3 Functional Genomics Laboratory.

“One reason may be that as a person ages, the olfactory stem cells age and are less able to replace mature cells, or maybe they are just depleted. So, if we had a way to promote active stem cell self-renewal, we might be better able to replace these lost cells and maintain sensory function,” he says.

The team determined that the regulatory gene called p63 is directly responsible for activating olfactory stem cells, so naturally researchers will focus their efforts on learning how to manipulate its function.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //