As a massive galaxy, the Milky Way is surrounded and orbited by a large number of smaller, dwarf galaxies. Ever since astronomers discovered this, they have been trying to determine what faith awaits our galaxy, and if future collisions and bombardments on the Milky Way's inner disk are possible. A new study has concluded recently that this is highly unlikely to happen. According to computer simulations, such collisions would most likely only “puff up” the galactic disk and form structures known by astronomers as stellar rings.

These stellar rings form mostly on the edge of galactic disks, experts say. In other places in the Universe, telescopes have resolved similar structures, which are called flares. The new investigation solves two mysteries at the same time, the Ohio State University (OSU) team that has been behind the study believes. First of all, it explained how future interactions would modify our galaxy, and, secondly, it gave an explanation for the Milky Way's “puffy” disk edges. The model revealed that such collisions definitely took place in the past as well, and would continue in the foreseeable future.

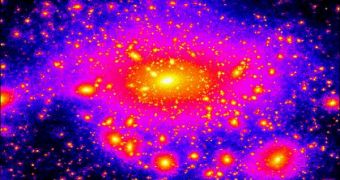

The current astronomical theories hold that galaxies exist in the Universe inside large halos of dark matter. Filaments of this dark matter conduct the galaxies to certain focal points, like the nods of a web. At these cosmic junctions, massive galaxies form, while smaller ones are pulled in their orbit. The new simulation, which is the most detailed of such a scenario to date, reassures us that there is no danger coming from these smaller galaxies, which include the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds.

“We can't know for sure what's going to happen to the Milky Way, but we can say that our findings apply to a broad class of galaxies similar to our own. Our simulations showed that the satellite galaxy impacts don't destroy spiral galaxies – they actually drive their evolution, by producing this flared shape and creating stellar rings – spectacular rings of stars that we've seen in many spiral galaxies in the universe,” OSU astronomer Stelios Kazantzidis explains.

“We know from cosmological simulations of galaxy formation that these smaller galaxies probably interact with galactic disks very frequently throughout cosmic history. Since we live in a disk galaxy, it is an important question whether these interactions could destroy the disk. We saw that galaxies are not destroyed, but the encounters leave behind a wealth of signatures that are consistent with the current cosmological model, and consistent with our observations of galaxies in the Universe,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //