Scientists with the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) are currently developing a new instrument, that is dedicated to studying a critical phenomenon called magnetic reconnection. The device will fly to space with an upcoming NASA mission.

For decades, experts have known that this process is responsible for underlying such phenomena as the production of solar flares and the generation of energetic polar lights called auroras. However, there has been no mission dedicated exclusively to studying it until now.

This will be the only goal of the Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission, which the American space agency plans to launch no later than 2014. It will include four identical spacecraft, that will feature instruments capable of teasing out the properties of magnetic reconnection.

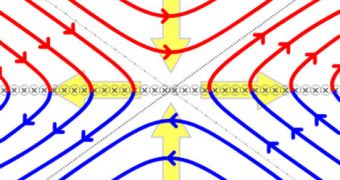

This phenomenon occurs when magnetic field lines collide with each other, and produce bursts of energy. The lines themselves may originate on the Sun, in our planet's upper atmosphere, or on another planet or moon, Science Blog reports.

The magnetic field lines produced by the Sun extend over million of miles, and they also interact with Earth's magnetic field. However, experts know very little about the way these two magnetic structures influence each other, as they never conducted an in-depth study of this interaction.

MMS will be able to conduct this type of investigations, and a critical part of its capabilities will be the Fast Plasma Instrument (FPI), which is now being developed at the GSFC, in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The thing about the FPI is that it will need to be more than 100 times faster than any other, similar instrument ever built. It will have to be able to produce a full map of the entire sky about 30 times each second. It will only pass through magnetic reconnection sites for less than a second at a time.

“Imagine flying by a tiny object on an airplane very rapidly. You want to capture a good picture of it, but you don’t get to just walk around it and take your time snapping photos from different angles,” explains scientist Craig Pollock.

“You have to grab a quick shot as you’re passing. That’s the challenge,” adds the expert, who is a co-investigator of the FPI instrument at the GSFC.

“Right now the state of reconnection knowledge is simply that we know it’s going on. One of the fundamental questions is to figure out what controls the process – the little stuff deep inside or the larger, external, boundary conditions,” adds Tom Moore.

The expert holds an appointment as an MMS project scientist at GSFC. “Some conditions produce a small burst of energy and sometimes, during what we think are the same external conditions, there’s a huge burst of energy,” he adds.

“That might be explained if the reconnection event depended crucially on what’s going on deep inside, in an area we’ve never been able to see before,” Moore concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //