Since the advent of the Greek civilization, philosophers have begun wondering whether we really possess free will, in the strictest sense of the term. They were curious to know whether human beings could indeed take completely independent decisions that were not in the slightest influenced by external factors, or other causal components. In the current society, it is a custom for scientists and laymen alike to consider free will as something that humans have from birth, but some disagree. Critics say that personal decisions are influenced by other factors to a great extent, and that, as such, we cannot speak of definite free will, PhysOrg reports.

One of the researchers who argue for this approach to defining the concept is University of Pennsylvania professor of biology Anthony Cashmore. He says that most of his colleagues even today refuse to accept the idea that humans are little more than conscious machines. We compute all our decisions based on environmental factors, other people's ideas, and most often past experiences, and cannot be trusted to make an entirely independent decision. In addition, our own body's chemical reactions at times conspire against us, making us feel nervous or too calm, and causing us to fail providing the most appropriate answer to a problem or a situation.

“I would like to convince biologists that a belief in free will is nothing other than a continuing belief in vitalism (or, as I say, a belief in magic),” says Cashmore. In a new study the expert conducted, he reveals that believing in human free will is very much the same thing as believing in religion, or gods. The laws of the physical world exclude both, and thus far no clear evidence to support their actual existence has been produced. The professor also aptly points out that people have no problem with accepting that “lower creatures,” all animals, plants and microorganisms included, are nothing but “bags of chemicals,” and yet, that they have such a hard time accepting the same to be true for them.

Some proponents to “human superiority” say that out deep capacity of abstraction and our level of intelligence and adaptability make us unique in the world. But recent studies have concluded that animals such as crows, elephants, primates, dolphins and whale – among many others – also have similar abilities, and in some regards exceed even our own. The thing that could indeed be pointed out as separating “us” from “them” is the subconscious mind, but Cashmore reveals that this is where we start treading on very fine ground.

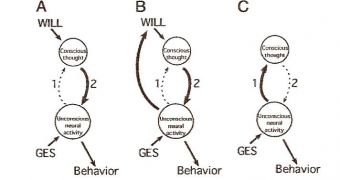

In previous studies, neuroscientists have proven that the human brain acts at both the conscious and unconscious levels at the same time. We experience a feeling that we are controlling our actions when the conscious mind steps in, but investigations have revealed that this level of awareness is second to the unconscious mind, which means that the latter takes preeminence. Given that we can't control it, any “suggestion” coming from it, as those rooted in something we heard years ago, or an experience we had when we were little, gets integrated in our decisions without us knowing it. In other words, it would take only the action of the conscious mind to make a decision that could be labeled as “free will,” and this is impossible.

“Whereas the impressions are that we are making ‘free’ conscious decisions, the reality is that consciousness is simply a state of awareness that reflects the input signals, and these are an unavoidable consequence of GES [genes, environment, and stochasticism]. Few neurobiologists would argue with the notion that consciousness influences behavior by acting through unconscious neural activity,” he said. “More controversial is the notion that consciousness plays a relatively minor role in governing our behavior. The conscious mind is conceivably more a mechanism of following unconscious neural activity than it is one of directing such activity,” Cashmore mentions.

“I find it interesting to compare this line of thinking with that of Freud, who created a controversy by suggesting that the unconscious mind played a role in our behavior. The way of thinking regarding these matters now has moved to the extent that some are questioning what role, if any, the conscious mind plays in directing behavior. Namely, Freud was right to an extent that was much greater than he realized,” he adds. Details of his study will appear in an upcoming issue of the respected journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //