A team of US astronomers announces the discovery of four faraway galaxies that are extremely bright, much more so than theoretical predictions would suggest. These cosmic formations are all much smaller than the Milky Way, and are classified as dwarf galaxies.

Regardless, they contain up to a 1 billion stars each, researchers said yesterday, January 7, at the 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), which is being held in Washington, DC. The team reported using data from the NASA Hubble Space Telescope and the Spitzer Space Telescope for this investigation.

The four objects the team identified lie more than 13 billion light-years away from Earth, meaning that we see them as they appeared when the Universe was just 750 million years old. Some theories explaining the early Universe argue that such formations should not have existed so early on in the history of the Cosmos.

Additionally, researchers from the University of California in Santa Cruz (UCSC) also presented the deepest image of a galaxy cluster ever obtained, which was produced during the same investigation.

One of the things that puzzled scientists about this study was that the four objects Hubble and Spitzer identified were around 10 to 20 times more luminous than any other found so far away in the Cosmos.

The dwarf galaxies are all roughly 1/20th the size of the Milky Way, but they contain 1 percent of its stars, and form new celestial fireballs at a rate 50 times higher. Our galaxy now produces about one new star per year, astronomers say.

“These just stuck out like a sore thumb because they are far brighter than we anticipated. There are strange things happening regardless of what these sources are. We're suddenly seeing luminous, massive galaxies quickly build up at such an early time. This was quite unexpected,” UCSC researcher Garth Illingworth said.

Using Hubble and Spitzer together in studying these bright galaxies enabled astronomers to calculate the stellar distribution – and the mass – of the dwarf galaxies with unprecedented precision.

“This is the first time scientists were able to measure an object's mass at such a huge distance. It's a fabulous demonstration of the synergy between Hubble and Spitzer,” said expert Pascal Oesch, who holds an appointment as an astronomer at the Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

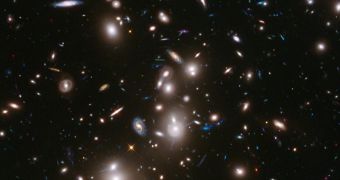

Since the objects were located so far away, Hubble had to use an observations technique called gravitational lensing to image them. The massive galaxy cluster Abell 2744 in the constellation Sculptor was used as a lens to amplify light emitted by extremely distant objects behind it.

The view revealed no less than 3,000 background galaxies, intermingled with foreground galaxies included in Abell 2744. Researches then had to browse observation data to find the most interesting cosmic formations.

Astronomers now plan to combine Hubble and Spitzer data with archive or new information from the NASA Chandra X-ray Observatory (CXO), in hopes that this will allow them to study the potential existence of black holes at the core of the four distant galaxies.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //