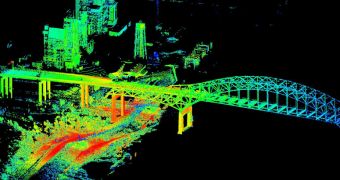

Using an advanced imaging and mapping technique, researchers at the US Geological Survey (USGS) were able to compile a 3D map of storm surges around the Interstate-510 bridge, in New Orleans, Louisiana. The dataset was produced on Friday, August 31.

Given the lessons taught by Hurricane Katrina – a Category 3 weather event that battered the city in 2005 – scientists and authorities are taking no more chances with underestimating the weather. The purpose of the new study was to map the urban flooding caused by Hurricane Isaac in Louisiana.

Using a device called a terrestrial lidar (T-lidar), the team was able to collect a wealth of data on sensitive areas in New Orleans, but also in Alabama and Mississippi. All three states experienced the effects of Hurricane Isaac's passing.

A lidar (Light Detection And Ranging) instrument can easily produce vast volumes of topographic data, by measuring numerous points in a given space over a very short time frame. A full, 360-degree view, takes just 4 to 5 minutes to compile.

The instrument is tremendously precise, and is able to generate high-resolution datasets that are extremely useful for monitoring landslides, floods, and other natural events. In the case of New Orleans, the map will be used to create a model of the city.

This model will then help scientists figure out which areas are most likely to be flooded during future storms, and which are able to endure storm surges without letting too much water through.

“If a picture paints a thousands words, a T-lidar scan paints several million words to capture the fleeting aftermath of a hurricane's impact,” explains the Director of the USGS, Marcia McNutt.

“The ability to rapidly preserve for posterity a quantifiable, three-dimension representation of storm damage is going to open the doors for new flood hazard science,” she goes on to say.

“Using terrestrial lidar in this fashion has the possibility of helping us quickly assess high-water marks, current water levels, and to some degree flood damage, in a very short time,” adds Athena Clark.

“We’re always looking for better, more efficient and cost effective ways of advancing the science and this technology has some great possibilities,” concludes the expert, who is the director of the USGS Alabama Water Science Center.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //