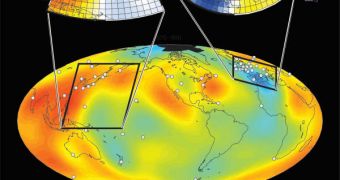

Thanks to the dedication of researchers and experts from the Oregon State University (OSU), we now have the first full map of the electrical conductivity in the Earth's mantle, at a global scale, and in 3D. The find could have some of the most useful applications, such as using disruptions in electrical conductivity to find water hidden under the planet's crust. Details of the amazing work appear in this week's issue of the respected scientific journal Nature.

According to the OSU team, most areas of high conductivity they mapped coincide with subduction zones. In these areas, tectonic plates that move on molten rock under the planet's crust slide underneath each other, generating earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunami waves.

“This work is important because it complements global 3-D seismic imaging of Earth's interior, which uses sound waves generated by earthquakes. Scientists may be able to combine these two methods to tease out a more detailed understanding of variations in Earth's inner composition, water content and temperature,” National Science Foundation (NSF) Division of Earth Sciences Program Director Robin Reichlin explains. The DES has funded the new work.

“Many earth scientists thought that tectonic plates are not likely to carry much, if any, water deep into the Earth's mantle. Our model, however, clearly shows a close association between subduction zones and high conductivity. The simplest explanation is water,” OSU geologist and paper co-author Adam Schultz adds. For quite some time, planetary scientists have wondered how much water, if any, can be found under the ocean floor, and just what quantities make their way into the mantle and how. The new research takes an important step forward towards understanding these processes.

“In fact, we don't really know how much water there is on Earth. There is some evidence that there is many times more water below the ocean floor than there is in all the oceans of the world combined. Our results may shed some light on this question,” OSU oceanographer Gary Egbert, who is also a co-author of the Nature paper, shares. Still, the experts do not want to get ahead of themselves. They believe that alternate explanations could exist on how water got in subduction zones.

“If it isn't being subducted down with the plates, is it primordial, down there for four billion years? Or did it come down as the plates slowly subduct, suggesting that the planet may have been much wetter a long time ago? These are fascinating questions for which we don't yet have answers,” Schultz says. As a result of these questions, the researches now plan to create the most comprehensive map on how much water is located under the crust, and where the most significant concentrations can be found.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //