Some of the most common, naturally-occurring biominerals, such as for example seashells, will soon be reproduced thanks to a new technique developed by investigators at the University of Leeds.

Researchers here were recently able to recreate synthetic crystals whose structures and properties closely mimic those of their natural counterparts. Details of how this was achieved were published in the latest issue of the esteemed scientific journal Nature Materials.

In the end, researches such as this are aimed at finding novel technologies for creating high-performance materials that only require environmentally-friendly conditions. In other words, minimizing the strain on diminishing resources and improving production times are top priorities.

Structures including bones, teeth and seashells are well-known sources of biominerals. More often than not, the chemicals display remarkable shapes, properties and structures that have intrigued scientists.

They set out in an effort to replicate them, finally succeeding after years of work. Biominerals are different from simple minerals through the fact that inorganic minerals in their composition (such as calcium carbonate) contains small amounts of organic materials, such as a protein.

The investigators who conducted the new mission were led by Professor Fiona Meldrum, who holds an appointment with the University of Leeds School of Chemistry. The most important aspect of the work was replacing proteins with nanomaterials.

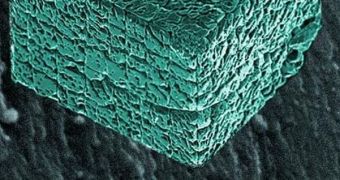

The team succeeded in growing calcite crystals while they were exposed to synthetic polymer nanoparticles that replaced artificial proteins. The composite material is created as the nanoparticles are included in the crystals during growth,.

“This method of creating synthetic biominerals gives us a unique insight into the structure of these incredible materials and the way the organic molecules are incorporated into the crystal structure at a microscopic level,” Meldrum explains.

“We can then relate this microscopic structure to the mechanical properties of the material,” he adds.

“What we found is that the artificial biomineral we have created is actually much harder than the pure calcite mineral because it is a composite material – where you add something soft to a hard substance to create something even harder than either of the constituent parts,” the expert reveals.

What surprised the team is that their synthetic 'pseudo' protein was able to replace the function that real proteins fulfill in naturally-occurring biominerals. This is something that the researchers were expecting to work on for many years.

Researchers from the University of Leeds, the University of Sheffield, Manchester University, the University of York, and the Israel Institute of Technology were a part of the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council-funded study.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //