A group of investigators led by scientists at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) will soon set sail for the western parts of the tropical Pacific Ocean. During their mission, the experts will analyze exactly how these remote waters influence air chemistry around the world.

Though this area is sparsely populated, and thus very little studied, it plays a critical role in determining the nature of the global climate. The new study will feature researchers from the University of Maryland and the University of Miami, NASA, and other universities and research centers in the US.

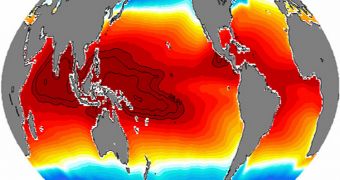

One of the reasons why the western tropical sector of the Pacific is so important it that it holds the hottest ocean water on Earth. When this heat evaporates into the atmosphere, the entire area becomes a chimney of sorts, which produces effects that circle the globe.

The purpose of the new investigation will be to understand how this effect will influence Earth's atmosphere as temperatures increase, and the Pacific starts producing more and more large storms. It is well known that such weather events can change oceanic heat release patterns, experts say.

According to data already available to researchers, the Pacific Chimney is responsible for lofting a huge amount of gases and particles from the water into the atmosphere, via massive thunderclouds that then move around the world, depositing their cargoes in random places.

“To figure out the future of the air above our heads, we need to go to the western Pacific. This region has been called the holy grail for understanding global air transport, because so much surface air gets lifted by the storms and then spreads globally,” says NCAR scientist and principal study investigator, Laura Pan.

The study effort is called Convective Transport of Active Species in the Tropics, or CONTRAST, and is supported by grants from the US National Science Foundation (NSF). The investigation will be based in Guam, Pan explains.

“Research results from CONTRAST will be extremely important for understanding the ozone-depleting effects of certain chemicals, such as short-lived halogen species like those containing chlorine and bromine, in the tropical upper troposphere and lower stratosphere,” concludes Sylvia Edgerton, who is a program director with the Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences at NSF.

CONTRAST will be coordinated with the Airborne Tropical Tropopause Experiment (ATTREX) conducted by NASA to study water vapors in the upper atmosphere, and with the Coordinated Airborne Studies in the Tropics (CAST), which focus on analyzing air properties near the ocean surface.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //