One of the most impressive things about our immune system is that it is essentially everywhere in the body. Where there's blood, there are bound to be at least a few white blood cells (WBC) just patrolling around and doing their job. When a chemical trigger runs through the blood, announcing that a pathogen has been discovered, all immune cells in the vicinity respond like police crews, and move to the specified location to eliminate the threat. But researchers have noticed that this no longer seems to be the case when the perpetrator is the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

Apparently, the pathogen has discovered ingenious ways of avoiding capture and annihilation, and now experts from professor Dr. Oliver Fackler's research group at the Heidelberg University Hospital Hygiene Institute Virology Department have discovered how it does that. The HIV Nef protein is the chemical the virus uses to destroy immune cells' mobility, and their response implicitly. In a scientific paper appearing in the latest issue of the highly respected journal Cell Host & Microbe, they highlight a possible direction that future HIV treatment options should take to counteract this protein.

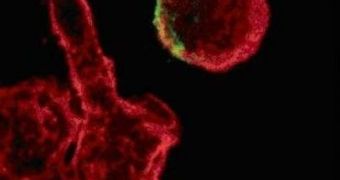

Immune cells of the T-helper type are the preferred target of HIV. They are not only engaged in direct combat with the intruder, but are also responsible for creating immune system-wide immunity to a pathogen. In order to establish this immunity, they need to be able to move. Usually, the cell structure element actin is responsible for allowing this, both in cells and in muscles. But the Nef protein has the ability to prevent actin from relaxing to its initial state after it performs an action.

This is absolutely necessary if actin is to be available for use again. Therefore, if it cannot revert to its original parameters, it cannot be used. Immune system cells become immobile, and are unable to hook up with each other and mount an all-out offensive against the virus. HIV then proceeds to infecting cells methodically, multiplying its numbers in the process, and eventually causing the death of the host cell. Fackler's team determined the exact mechanism through which Nef acted.

In their studies of zebrafish embryos, they noticed that the HIV protein influenced an enzyme that usually had nothing to do with cell mobility into deactivating a regulator for actin regeneration. The reorganization of actin is hampered, and cells become immobile. “We speculate that the negative effect of Nef on the mobility of T-helper cells has far reaching consequences for the efficient formation of antibodies by B-lymphocytes in the patient,” the professor says.

“The mechanism we have described could be involved in the increasingly observed malfunction of B-lymphocytes in AIDS patients,” he adds. Existing treatments do not address the Nef protein, e! Science News informs, but that is about to change. Now that one of the primary action mechanisms of HIV has been deciphered, future, experimental cures will most likely focus on counteracting the effects of this protein. However, HIV has a host of mechanisms that protect it from the immune system, so the struggle against it is far from over.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //