According to a group of experts, exoplanets that feature continents and oceans on their surfaces should flicker in response to light hitting them. They base their idea on the fact that this is precisely what happens when sunlight strikes Earth, as viewed from a distance. However, scanning for flickers on other worlds is not as easy as it may seem at first, given the huge distances involved. Telescope mirrors would need to get impressively large, and we're taking diameters of thousands of kilometers here. It stands to reason that this is impossible to create, and now scientists propose a way around this, Space reports.

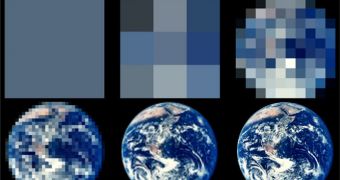

The new method relies on comparing the color and intensity changes that light suffers when it hits our planet, as viewed from tens of light-years away. Needless to say, Earth is fairly unique, at least in our immediate vicinity. It features numerous lifeforms on its surface, below the ground and in the air, and it is mostly covered in oceans. Experts say that all these factors contribute to our planet exhibiting shifting colors as viewed from a static reference point. As the Earth turns, the proportions of continents and oceans in an observer's field of view changes, and therefore the planet appears to flicker.

Using the distinct color palette that researchers just created, it may become possible to identify similar traits on exoplanets as well, the team behind the accomplishment says. By using this method, “we can infer the surface composition of the [exo]planet,” explains University of Tokyo doctoral student Yuka Fujii. The scientist was also the lead author of a new paper detailing the findings, which appears in the May 4 issue of the esteemed scientific publication The Astrophysical Journal. One of the main issues found associated with exoplanetary research is using visible light wavelengths for the job.

Generally, of the 400+ exoplanets identified thus far, most are simply detected as points of light, which are laboriously extracted from the overall glare of their parent stars. Most of them are gas giant-sized objects, and so finding an Earth-size planet is even more difficult. But observing its surface directly, and determining the presence, or absence, of oceans and forests is still a thing of science-fiction today. “It is hard to obtain enough photons from distant planets for detection,” explains Fujii. “We cannot directly identify green, blue and red spots on the surface. But we can observe the total color average over the visible surface of the planet,” he adds, saying that comparisons to the new palette could then reveal additional details about the possible appearance of the planet's surface.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //