According to a new set of astronomical observations, it may be that one of the 400 exoplanets thus far discovered is not an exoplanet after all. The celestial body, which lies some six parsecs away from our solar system, was detected by ground-based observatories earlier this year, and, if the findings turn out to be bogus, it would deal a tremendous blow to ground-based telescopes. The new investigation also sheds some doubt on a technique known as astrometry, which observes the side-to-side motion of a star in order to detect if an orbiting body around it is altering its trajectory, Nature News reports.

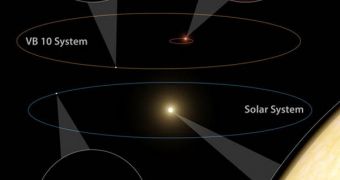

The exoplant was allegedly found in May, when astronomers used a telescope at the Palomar Observatory, in southern California, to look at a star about one thirteenth the mass of the Sun. The investigators, who were led by Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) expert Steven Pravdo, said at the time that the star, known as VB10, was being orbited by an exoplanet roughly six times the mass of Jupiter.

The find raised new hopes that astrometry was a viable research method, and one whose results could be relied upon. Now, a group of German researchers based at the Georg-August University in Gottingen say they took a different approach to looking for the planet, and that the body is simply not there.

“The planet is not there,” expert Jacob Bean, who has been the leader of the new research, says. He and his team used an established astronomical detection method known as radial velocity to look for the exoplanet. This technique is the one used to discover most of the planets outside the solar system found up to this point. In radial velocity, experts look at variations in the lines of a star's absorption spectrum, so as to determine if an orbiting object moved in front of it for a length of time. Bean used the European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Very Large Telescope (VLT), in Chile, to look at VB10's variations in the infrared regions of the spectrum, where the star was most active.

“We would definitely have seen a significant amount of variation in our data if [the planet] was there,” the team leader says, adding that a paper detailing his team's conclusions has already been submitted for publishing to the Astrophysical Journal. “Unfortunately, astrometry is a very difficult business,” Bean adds, because interferences from the Earth's atmosphere can lead scientific conclusions on a wrong path.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //