The fact that the human body contains millions of species of bacteria living in symbiosis is well known, as is the fact that we would die immediately if these microorganisms were removed from within us. However, when humans do not co-evolve with these microbes, diseases can occur.

Such is the case with stomach cancer, researchers at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee determined in a new study. Their work was centered on the Andes Mountains town of Tuquerres, and the nearby coastal town of Turnaco, both in Columbia.

In Tuquerres, the incidence of stomach cancer is the highest in the world, with nearly 150 in 100,000 people developing this condition. By comparison, the incidence of the condition in Turnaco is just 6 cases for every 100,000 people. The towns are located just 200 kilometers (124 miles) from each other, Nature News reports.

The research team conducted the study to uncover the reason why this 25-fold difference exists between these two towns. The research determined that evolutionary mismatches between the inhabitants of Tuquerres and their microbial populations lead to this condition.

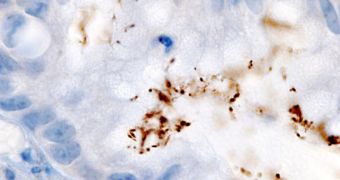

The main culprit is the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which is the leading cause of stomach cancers around the world. In most people, the organism does not produce tumors, but it can go haywire in some individuals, and destroy their stomach lining and flora.

Humans and H. pylori have a long common history, spanning back to when our first ancestors left Africa. However, in places such as South America, the arrival of new people – such as the colonialists – disrupted co-evolutionary patterns, and lead to a higher incidence of stomach cancers.

Vanderbilt investigators Pelayo Correa and Scott Williams, the leaders of the study, found that these mismatches are responsible for turning normal, benign infections into cancerous ones. Their discovery highlights a possible early prediction and detection tool for at-risk individuals.

“A lot of people have H. pylori, but very few have bad outcomes. Is that due to the organism or the host? This paper provides evidence that the fit is important. It’s a very nice advance,” comments New York University School of Medicine microbiologist Martin Blaser.

Details of the work are published in the latest early online issue of the esteemed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The team now plans to conduct a similar investigation in areas of eastern Asia, where the incidence of stomach cancer reaches as high as 42 cases in 100,000 men, and 18 cases in 100,000 women.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //