A group of astronomers has recently learned that the south pole region of the moon Enceladus is emanating a lot more heat energy than Earth's most active geologic hot spot, the Yellowstone Volcano.

This is completely unexpected, especially considering that the average temperatures on the Saturnine moon are around -198 degrees Celsius (around -324 degrees Fahrenheit). Its polar regions are even colder than that, and yet they release vast amounts of heat.

The discovery was made using the advanced suite of scientific instruments aboard the NASA Cassini orbiter. The spacecraft arrived at Saturn on July 1, 2004, and has been orbiting the gas giant, its rings and its moons ever since.

Data collected over the years indicates that the south pole of Enceladus produces as much as 15.8 gigawatts of heat-generated power, more than 2.6 times the output of all the hot springs in the Yellowstone National Park.

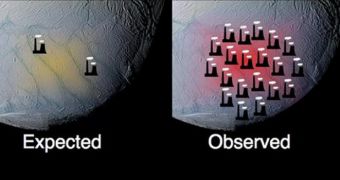

According to scientists, this amount of energy is 10 times larger than they were expecting to find.

The most important implication of this discovery is that the moon indeed features an ocean of liquid water beneath the thick ice crust covering its surface. Still, that does not explain where all the heat is coming from, planetary scientists add.

“The mechanism capable of producing the much higher observed internal power remains a mystery and challenges the currently proposed models of long-term heat production,” says expert Carly Howett.

The expert, who holds an appointment at the Boulder, Colorado-based Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), is the lead author of a new study detailing the findings. She made the announcement in a NASA statement released Monday, March 7, Space reports.

Most thermal activity on Enceladus is concentrated alongside its tiger stripes, a set of four, roughly-parallel fissures at the south pole, which are all some 80-by-1.2 miles (130-by-2 kilometers).

They produce geysers, through which organic molecules and water vapors are expelled from the moon's interior. All of this material then goes on to feed Saturn's E ring.

Details of the new study appear in the March 4 issue of the esteemed Journal of Geophysical Research.

“The possibility of liquid water, a tidal energy source and the observation of organic [carbon-rich] chemicals in the plume of Enceladus make the satellite a site of strong astrobiological interest,” Howett concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //