It is global warming at a smaller scale. When El Ni?o begins, the deserts of the Peruvian coasts are turned to lakes, but great floods, violent cyclones, severe droughts and harsh winters occur worldwide, triggering hunger, epidemics, huge wildfires, and damages on crops, goods and environment. The most affected zones are California, Canada, China, Indonesia, Pakistan, parts of Africa, Peru, Bolivia.

El Ni?o is the warm oceanic current that emerges off the Peruvian coasts every 2 to 7 years. Because the warm current appears usually around Christmas, the old Spanish sailors named it El Ni?o ("the Baby" in Spanish, alluding to the birth of Jesus).

In Peru, warming means higher rainfalls and larger herds. Nevertheless, the warm layer impedes the colder waters bellow, rich in nutrients, to get up. In this case, the sea productivity drops, and many sea birds migrate. The warming by 5o C of the ocean waters kills many coral reefs.

Fluctuations of El Ni?o cause huge natural mortalities in the species depending on the sea resources, as their food (fish, crustaceans, corals and algae) dies or gets scarce. In 1982-1983, this phenomenon cut to half the populations of sea lions and sea birds of Galapagos Islands and the sea iguanas were menaced with extinction, as the green algae that they fed on were replaced, due to the higher temperatures, by brown algae, which they could not digest. Instead, the rains boosted the growth of the plants, the insects and insectivorous bird populations.

However, beyond the material damages, the El Ni?o phenomenon influences profoundly the health conditions as well. Transmissible diseases experience booms during this phenomenon. In 1993, El Ni?o caused a rise of the cases of viral encephalitis transmitted by the Culex mosquitoes. The same phenomenon caused the epidemics of "Japanese encephalitis" in India in 1973 and "Nile Valley fever" in Africa in 1974.

In Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru and Pakistan, the recurrent epidemics of malaria are connected to the massive increase of the mosquitoes, caused by abundant rainfall brought by El Ni?o. Another malady boosted by El Ni?o is the cholera.

El Ni?o and the monsoon

El Ni?o also can cause the fail of the monsoons and agricultural losses in countries like India.

In 1997, a predicted drought did not occur but, in 2002 and 2004, unexpected and severe droughts surprised an unprepared country. The key is determining exactly where in the equatorial Pacific the sea-surface warming is strongest. When the warm waters are closer to the coast of South America in eastern Pacific, the effects of the monsoon are weaker or nonexistent. In the eastern Pacific waters, where the Humboldt current greatly cools the water, more warming has to occur to increase temperatures over a limit, before affecting India's rains. When El Ni?o strongly heats the central Pacific waters, the result is drought in India.

The reason is that, as the central Pacific warms, the atmosphere above it heats up and rises. This induces a large, dry air mass to sink over India, depriving it of the monsoon. In the western Pacific, where sea-surface temperatures are among the warmest in the world, less additional warming can increase the amount of rainfall during the monsoon. Western El Ni?os cannot have a serious influence on the monsoon. Rising ocean temperatures due to global warming may reinvigorate the monsoons, which have past through a decline over the past three decades.

How does El Ni?o emerge?

El Ni?o emerges because of the water movements in the Pacific. When the sun warms the waters in the Western Pacific (off Indonesia and Australia), the wet hot air rises, generating an area of low pressure. The climbing air mass cools down, forming water vapors that generate rains in that region.

The dried air is pushed eastwards by the winds in the upper atmosphere. Moving eastwards, the air mass cools further, becoming heavier and, above the Ecuador, it starts descending.

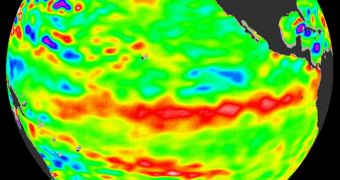

This determines the appearance of a high pressure zone. At lower altitudes, the tradewinds move back westwards, to Indonesia, ending the cycle. The tradewinds act like a breeze, pushing the hot air towards western Pacific, so the sea level here is 60 cm higher, and the waters are 8 degrees C warmer. In the eastern Pacific, the colder and nutrient-rich bottom water climbs to the surface, so the marine life blooms. Thus, in normal years, without El Ni?o, the surface temperatures are lower in the east than in the west.

For reasons that are not yet clearly known, at intervals of a few years, the tradewinds decrease in intensity or even cease. When these winds weaken, the warm water accumulated off the Indonesian coasts heads eastwards, thus the water temperature off South American coasts rises. This removes the zone of abundant rainfall from western Pacific to east, in central and east Pacific.

But El Ni?o event can affect climate further than the Pacific area, to India and South Africa. At higher altitudes, El Ni?o becomes stronger, and replaces the winds called jet streams, which move eastwards at high speeds. The jet streams dictate the movement of the hurricanes.

Increasing or shifting the direction of these currents means harsher or less severe seasonal storms or weather conditions. For example, in the winters with El Ni?o, the weather is milder in northern US, and wetter and colder in southern states. Currently, El Ni?o forming conditions are monitored in Pacific by balizes measuring water parameters, until 500 m depths. The data are stored in computers that make prognoses.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //