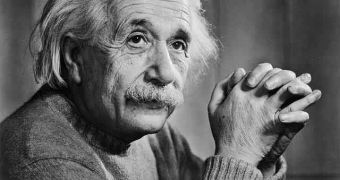

A thorough look back through scientific history indicates that the major breakthroughs were the result of the genius and hard work of single gifted individuals rather than to the collective effort of savants working under institutional umbrellas. Einstein, Newton, da Vinci or Copernicus stand out as vivid examples to this statement, in spite of the rush for knowledge and discoveries that major institutions have enrolled in for about half a century.

A recent theory developed by a US engineer of Romanian origin, Adrian Bejan from Duke University, identified the starting point of this teaming up process as the Russian's launch of their Sputnik satellite on October 4th 1957. That event caused the US to substantially increase their funding of massive research groups in various scientific institutions. But generally, large groups of scientists are not a very fertile environment for great ideas.

Bejan also points out that none of the extremes is best suited for the ultimate goal, "If an institution is made up only of solitary researchers, it would have many ideas but little support," he explained, as quoted by Live Science. "On the other hand, a group that is large for the sake of size would have a lot of support, but would comparatively have fewer ideas per investigator." The best approach, and most scientifically-oriented, he believes, is a fortunate, natural and successful combination of the two.

"Successful research groups are those that grow and evolve on their own over time," shared the Duke expert. "For example, an individual comes up with a good idea, gets funding, and new group begins to form around that good idea. This creates a framework where many smaller groups contribute to the whole." His theory cannot predict, though, when the next Einstein may appear, especially since the time gap between Newton and Einstein, who were considered close in terms of intellectual prowess, was about two centuries.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //