In a recent paper in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, researchers with UK's York University detail the development of a test which they say, although very simple and surprisingly straight-forward, can successfully be used to detect Alzheimer's before dementia sets it.

More precisely, the test serves to show which people are more likely to develop this condition at some point in their lives. Interestingly enough, it boils down to studying thinking and movement patterns to determine underlying cognitive issues.

The easy-peasy test for Alzheimer's

Writing in Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, Professor Lauren Sergio and PhD candidate Kara Hawkins explain that, as part of this research project, they had several volunteers complete a series of four visual-spatial and cognitive-motor tasks.

These tests were different in terms of difficulty, meaning that, whereas the first two were not all that demanding, the other ones forced the volunteers to give it their best shot to successfully complete the tasks, Medical Express informs.

The end goal was to determine how the people taking part in these experiments reacted when forced to think before performing one movement or another. It was thus discovered that the volunteers who had already shown to have a higher risk to develop Alzheimer's had a more difficult time completing the tasks.

“We included a task which involved moving a computer mouse in the opposite direction of a visual target on the screen, requiring the person's brain to think before and during their hand movements.”

“This is where we found the most pronounced difference between those with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and family history group and the two control groups,” Faculty of Health Professor Lauren Sergio explained in a statement.

What the researcher meant is that, when compared to the individuals who did not have a family history of Alzheimer's and the ones who were not suffering from mild cognitive impairment, the folks documented to have a higher Alzheimer's risk had a slower reaction time and moved at a slower pace.

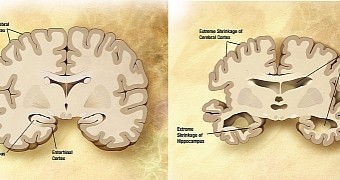

What's more, their movements were not as accurate and as precise as the movements of the people in the other two groups. “The impairments observed in the participants at increased risk of Alzheimer's disease may reflect inherent brain alteration or early neuropathology,” Lauren Sergio explained these findings.

So, is this oddly simple test any good?

As mentioned, this test cannot be used to actually diagnose Alzheimer's. It can, however, serve to identify those individuals who are more likely to develop this disorder as a result of faulty wirings in their brain.

Further investigations into the differences between the brains of people who have a higher risk to develop Alzheimer's and those of healthy individuals could lead to a better understanding of this condition, maybe even pave the way to treatment options.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //