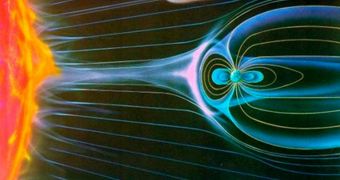

During a planetary alignment that took place on January 6, 2008, researchers at the European Space Agency (ESA) conducted a series of investigations meant to determine whether Earth's magnetosphere is indeed essential for our survival here. They found out that this was indeed the case.

While scientists have been suspecting that to be the case for a long time, they lacked the necessary evidence to state it as a fact. During the alignment, they got the chance to conduct a comparative analysis of the magnetospheres surrounding Earth and Mars.

The Cluster mission was used to study the way our planet's magnetic field behaved during the event, while the Mars Express orbiter was responsible for conducting similar studies around the Red Planet.

What scientists were especially interested in was figuring out how much protection the magnetosphere provided, compared to Mars' naked atmosphere. They learned that, indeed, life could have not endured on the neighboring world once the dynamo effect concluded.

One of the most important things the study group determined was that, without the magnetosphere, our planet's atmosphere would literally be stripped away, and thrown into the dark recesses of deep space.

This was made obvious when experts analyzed the amounts of oxygen the two atmospheres lost on account of solar wind. Data from Cluster and Mars Express revealed that the Red Planet at times lost as much as 10 times more oxygen than Earth.

Over billions of years, this difference would have catastrophic consequences. Astronomers believe that the process they observed during the planetary alignment is one of the reasons why our neighboring planet has such a tenuous atmosphere.

“The shielding effect of the magnetic field is easy to understand and to prove in computer simulations, thus it has become the default explanation,” Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPI-SSR) expert Yong Wei explains.

Scientists “now hope to extend their work by incorporating data from ESA’s Venus Express spacecraft, which also carries a sensor that can measure the loss of its atmosphere,” a press release from the organization announces.

“Venus will provide an important new perspective on the issue because like Mars, it has no global magnetic field, yet it is similar in size to Earth and has a much thicker atmosphere,” the statement concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //