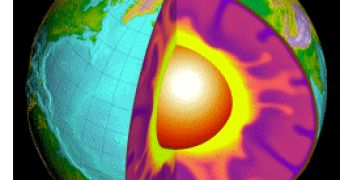

The length of a day is not affected only by tides and winds. Underground forces are prolonging our days by milliseconds, as revealed by a new research published in the journal "Science." Phenomena from the mineral layer at the core-mantle boundary, 1,615 mi (2,600 km) deep, appear to impact the Earth's spinning speed.

"The length of a day ? is changing due to the interaction between the mantle and the core in the very deep Earth. This is basically because the bottom of the mantle has very high electrical conductivity," said co-author Kei Hirose, a geoscientist at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, in Japan.

The Japanese team made a lab simulation of the physical traits of the deep mantle in order to investigate how minerals in Earth's lower mantle act. The mineral post-perovskite was put under the high pressure registered in the deep mantle between the points of two 0.2-carat diamonds. The mineral was heated with a laser to 4,900? F (2,704? C). These factors boomed the electric conductivity of the mineral.

"This means that we have lots of electricity at the bottom of the mantle, which is coming from [Earth's] core," Hirose said.

"What this means is that the magnetic field in the core can grab onto, or lock into, the lowermost mantle. And so one of the influences that this can have is in altering the length of day, or the rotation rate of the Earth, depending on when and where the core is grabbing onto the mantle," Raymond Jeanloz, an Earth and planetary scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, told National Geographic News.

"This interaction accounts for several milliseconds of increase in day length over the past 150 years. Such minuscule time periods might seem negligible, but they do matter," said Hirose.

"We do care about Earth's rotation, because you really want to know, at any given time, where a spot on the surface of the Earth is relative to its orbit. That's why agencies like NASA have cared a lot about the Earth's rotation over the years," Quentin Williams, an Earth and planetary scientist at University of California, Santa Cruz, told National Geographic News.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //