According to the conclusions of a new study, it would appear that the reason why early whales have abnormally-shaped head is because this enabled them to use acoustics to discover the locations of things underwater. These shapes were not merely an adaptation that occurred later on.

For many years, researchers have believes that whales' heads took on a funny shape because they were attempting to provide a hardware background, if you will, for their amazing echolocation abilities.

What the new study suggests is that the peculiar shapes their heads had were not exclusively used to track the direction of sounds under the waves. The researcher was carried out by experts at the University of Michigan, and was funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF).

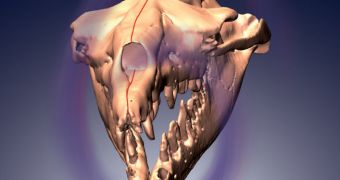

Details of the investigation were published in this week's online issue of the esteemed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The team says that modern odontocetes (toothed whales) are well known for their asymmetric skulls.

Another distinctive factor is the highly modified nasal structure that each of these animals have. This construct is the source of a whale's biological sonar. The latter helps it navigate the ocean, stay in touch with other whales, and find food.

At this point, there are only two whale groups still living on Earth. The second one, mysticetes (baleen whales), are not capable of echolocation, and so they feature perfectly symmetrical skulls. Most other species do to, even bats.

In the past, experts assumed that the ancestor of all whales – a group of animals called archaeocetes – in fact had symmetrical skulls, and that asymmetry developed alongside the ability to echolocate in toothed whales.

But the work of University of Michigan paleontologist Julia Fahlk and her team demonstrated that asymmetry in fact developed earlier on than past studies suggested. She explains that the characteristic was part of a suite of traits that allowed the whales to hear directionally while submerged.

“This means that the initial asymmetry in whales is not related to echolocation,” Fahlke explains. She worked closely with University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology scientist and colleague Philip Gingerich for this study.

“Modern whales don't chew their food. Toothed whales just bite it and swallow it, and baleen whales filter-feed. But archaeocetes have characteristic wear patterns on their teeth that show that they've been chewing their food,” the team leader says.

The new discovery, made possible by additional funds from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and the National Geographic Society, provide paleontologists and evolutionary biologists with new avenues of research for understanding how whales evolved.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //