An international group of researchers was recently able to gain a deeper understanding of the earliest vertebrate animals to walk on land. The so-called tetrapods (four-legged animals) are the earliest types of limbed vertebrates ever to step out of the ocean. The new investigation found that these creatures were still in the habit of feeding underwater, rather than on land.

These conclusions are based on an in-depth study of jaws found in ancient tetrapod samples. The work was carried out by scientists at the University of Zürich in Switzerland, and the University of Lincoln, the University of Bristol, and the University of Cambridge, all in the United Kingdom.

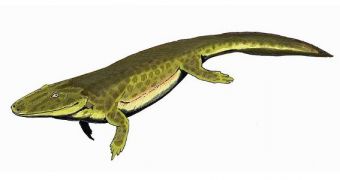

The team sought to understand the feeding mechanisms employed by an early tetrapod species called Acanthostega. The most spectacular specimens in this species were discovered back in 1987 in Greenland. Ever since, the fossils represented the focal point of a fiery debate on early tetrapods among the international scientific community.

Tetrapods represent a vast group of life forms, including amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. As one of the first such creatures to ever appear on Earth, Acanthostega plays a very important role in understanding how these creatures lived, walked, fed, and eventually occupied the land masses.

The new study enabled the team to infer the feeding mechanism this animal used. Scientists were surprised to learn that it most likely still fed underwater, rather than take its prey and consume it on land. This creature lived towards the end of the Devonian period, some 360 million years ago.

Scientists look at it as the perfect missing link between fish and tetrapods, which is why the UK-Swiss research team chose it as the subject of their advanced statistical research methods. The animal's lower jaw appears to have been more adapted for feeding underwater, retaining more fish than tetrapod characteristics.

“The origin of tetrapod from fish is an iconic example of a major evolutionary transition. The fossils of Acanthostega continue to play an unsurpassed role in our understanding of the fish-tetrapod transition,” explains Dr, Marcello Ruta, who holds an appointment with the School of Life Sciences at UL.

“Its broad snout appears to be consistent with aquatic feeding habits (suction feeding), but its complex cranial joints appear to be similar to those of terrestrial vertebrates and would suggest direct biting on land environments as a means of prey capture. This paradox prompted our study,” he adds, quoted by PhysOrg.

The team discovered rearward-facing anterior fangs and upturned anterior extremities in the fossils. Both are findings that suggest a scenario where Acanthostega was capable of a fast snapping action with its snout. Based on this, researchers concluded that the animal still hunted and consumed its prey underwater.

“All these observations imply that this type of jaw was capable of fast closure for efficient capture of fast prey, in support of a predominantly if not exclusively aquatic feeding action,” Ruta concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //