The idea that ancient humans were hunters is now being seriously challenged. According to new research, primates, including early humans, evolved not as hunters but as prey of many predators, including wild dogs and cats, hyenas, eagles and crocodiles.

"Our intelligence, cooperation and many other features we have as modern humans developed from our attempts to out-smart the predator," says Robert W. Sussman, who describes his theory in the book "Man the Hunted: Primates, Predators and Human Evolution" co-authored by Donna L. Hart.

Sussman studied the fossil record of humans and other primates and found very interesting things, in flat contradiction with the prevailing view. The idea of "Man the Hunter" is the generally accepted paradigm of human evolution, says Sussman, "It developed from a basic Judeo-Christian ideology of man being inherently evil, aggressive and a natural killer. In fact, when you really examine the fossil and living non-human primate evidence, that is just not the case."

The scientists studied the fossil evidence dating back nearly seven million years. "Most theories on Man the Hunter fail to incorporate this key fossil evidence. We wanted evidence, not just theory. We thoroughly examined literature available on the skulls, bones, footprints and on environmental evidence, both of our hominid ancestors and the predators that coexisted with them."

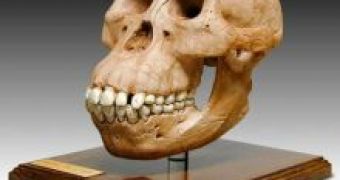

Given the amount of available data and the fact that human evolution was far from a straight line, but more like a tree, the scientists decided to look in most detail on one species. They chose Australopithecus afarensis, which lived between five million and two and a half million years ago, on one hand because of the large amounts of available data and on the other hand because it is recognized as a common link between fossils that came before and those that came after. It shares dental, cranial and skeletal traits with both. It wasn't an evolutionary dead-end.

"Australopithecus afarensis was probably quite strong, like a small ape," Sussman says. Adults ranged from around 1 to 1,5 meters and they weighed 27-45 kilograms. They were basically small bipedal primates. The most important discovery Sussman and Hart made about this ape-man is that it was not dentally pre-adapted to eat meat. "It didn't have the sharp shearing blades necessary to retain and cut such foods," Sussman says. "These early humans simply couldn't eat meat. If they couldn't eat meat, why would they hunt?"

According to researchers, eating meat became possible to humans only after fire was controlled. Hunting was also possible only with the help of tools. However, the first tools only appeared around two million years ago. And fire wasn't used until after 800,000 years ago. "In fact, some archaeologists and paleontologists don't think we had a modern, systematic method of hunting until as recently as 60,000 years ago," Sussman says.

"Furthermore, Australopithecus afarensis was an edge species. They could live in the trees and on the ground and could take advantage of both. Primates that are edge species, even today, are basically prey species, not predators," Sussman argues.

When scientists studied the fossil record for traces teeth and talon marks, they found that approximately 6 percent to 10 percent of early humans were preyed upon. The predation rate on savannah antelope and certain ground-living monkeys today is also around 6 percent to 10 percent.

The predators that lived 5-3 million years ago were not only larger than today, but they also were 10 times as many. The predators included hyenas as big as bears, saber-toothed cats and many other mega-sized carnivores, reptiles and raptors. In contrast, Australopithecus afarensis had neither big teeth nor tools and it was only a little taller than 1 meter. He was using his brain, agility and social skills to get away from these predators. "He wasn't hunting them," says Sussman. "He was avoiding them at all costs."

Sussman and Hart argue that many of our modern human traits, including those of cooperation and socialization, developed as a result of being a prey species. These traits did not result from trying to hunt for prey or kill our competitors, says Sussman, they resulted as a consequence of early human's ability to out-smart the predators.

"One of the main defenses against predators by animals without physical defenses is living in groups," says Sussman. "In fact, all diurnal primates (those active during the day) live in permanent social groups. Most ecologists agree that predation pressure is one of the major adaptive reasons for this group-living. In this way there are more eyes and ears to locate the predators and more individuals to mob them if attacked or to confuse them by scattering. There are a number of reasons that living in groups is beneficial for animals that otherwise would be very prone to being preyed upon."

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //