Exoplanets were theoretical not that long ago. Now thousands have been discovered. Most of those are huge gas giants, not unlike our Jupiter and Saturn, though sometimes even larger than that. Some of them are smaller, rocky planets, like the inner-planets of our Solar System, like our Earth.

Even among those, most are bigger than Earth, the biggest rocky planet in our Solar System, several times so. They're called Super Earths.

This leaves us with very few exoplanets that are comparable to Earth in size.

And again, most of those lie in places that would make them inhospitable to life, many are very close to their star and many times hotter than our planet.

Still, while finding exoplanets of any kind is cool, most people can agree that finding the ones that could potentially harbor life, at least as we know it, is the big goal.

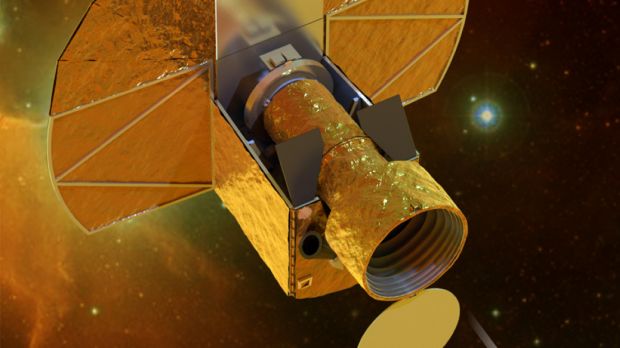

This is where ESA's Cheops space telescope comes in. The European Space Agency announced that it was now working on an instrument to detect exoplanets which would allow for the discovery of smaller planets than ever and even provide a glimpse at the atmosphere of those planets.

ESA has been trying to get an exoplanet-hunting program off the ground, literally, for more than a decade.

Budget cuts and setbacks have prevented it from doing that and meant the death of several such projects.

Now, ESA hopes that its latest project, CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite, or Cheops, won't share the same fate. Cheops is designed to detect exoplanets through what is known as the Transit Method.

When planets get in front of their stars, from our perspective, a decrease in the amount of light reaching is detectable. This dimming and its characteristics, i.e. how fast it happens, how much the light is dimmed, provides data on the planet causing it, specifically its radius.

That's the method used by Kepler to track down extrasolar planets, it's main advantage being that it can "scan" huge parts of the skies at the same time and discover many, many planets at the same time, something Kepler has been doing to great success so far.

Cheops though is more about the finer detail than about volume, its goal is to find smaller planets than it has been possible so far while also identifying those with a significant atmosphere. It will look for planets ranging from those the size of Earth to those about as large as Neptune.

Cheops is set for launch in 2017 with a planned mission of 3.5 years. It will sit in low Earth orbit, 800 km above our planet.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //