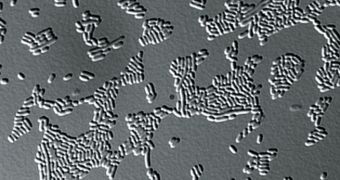

In a finding that confirms the existence of altruism among microorganisms, researchers at the Boston University discovered recently that Escherichia coli bacteria take care of each other when faced with a common enemy.

When subjected to the actions of an antibiotic, the microorganisms unite their forces, cooperating so that they can resist the assault. The tactic ensures that at least some bacteria endure.

According to the research team, some of the bacteria, whom natural genetic variation made invulnerable to the drug, can secrete substances that help the entire colony survive.

This means that even cells that would otherwise be considered to be competitors are protected. Therefore, a handful of E. coli bacteria can make an entire colony invulnerable to antibiotics.

The Boston group published the full results of their work in the September 2 issue of the top-rated scientific journal Nature. The data could be used to develop new means of addressing drug-resistant pathogens.

“Antibiotic resistance is a global health issue and we want to understand how and why bacteria become resistant to a particular antibiotic,” explains Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) biophysicist Hyun Youk.

Whenever E. coli becomes resistant to drugs, it released a molecule known as indole, which helps the bacteria tolerate stress exerted by the environment.

Not all of the microorganisms produce the compound, but those who do share it with their neighbors, essentially extending a protective shield overhead. If they don't do so, the other bacterial cells die.

“These E. coli cells have developed a very cunning strategy. [This study] highlights how difficult it will actually be to fight off antibiotic resistance,” the scientist adds.

“We were surprised,” says BU bioengineer James Collins of making the discovery. The team found the defense mechanism by accident, adds Collins, who was also the coauthor of the investigation.

“We immediately thought that the resistant guys must be producing something to help out the less resistant guys,” he goes on to say.

“It may be that the bacterial populations evolved this as a strategy to help survive transient stresses as a population,” Collins concludes, quoted by Science News.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //