A group of engineers from the Advanced Space Concepts Laboratory (ASCL) at the University of Strathclyde were recently able to demonstrate that displaced orbits are possible. Hypothesized more than 25 years ago, this peculiar family of orbits was calculated as possible, but thought impossible by the international scientific community. Back in 1984, renowned American space pioneer Dr Robert L Forward proposed that satellites could be made to orbit the Earth outside of the generally-accepted geostationary orbits above the Equator.

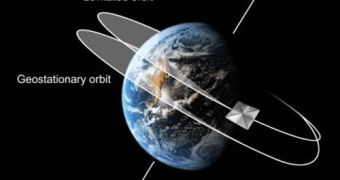

In other words, he believed that it could be possible to place spacecraft in orbit at higher northern and southern altitudes than it was though viable at the time. Dr Forward's work was prompted by the growing need that nations had of deploying increasing numbers of communications satellites around the planet. Generally, countries use geostationary orbits for the job, which circle the planet alongside the Equator. What the space pioneer proposed was using a large solar sail to nudge the spacecraft off-course, and into the displaced orbit.

The unusual dynamics involved in this proposition made the international scientific community see it as impossible to achieve. “Satellites generally follow Keplerian Orbits, named after Johannes Kepler – the scientist who helped us understand orbital motion 400 years ago. Once it's launched, an unpowered satellite will 'glide' along a natural Keplerian orbit,” explains the director of the ASCL, professor Colin McInnes. He conducted the work alongside graduate student Shahid Baig, and published the results in the latest issue of the esteemed publication Journal of Guidance, Control and Dynamics.

“However, we have devised families of closed, non-Keplerian orbits, which do not obey the usual laws of orbital motion. Families of these orbits circle the Earth every 24 hours, but are displaced north or south of the Earth's equator. The pressure from sunlight reflecting off a solar sail can push the satellite above or below geostationary orbit, while also displacing the center of the orbit behind the Earth slightly, away from the Sun,” the team leaders adds.

At this point, solar sail technology does not allow for displacements larger than 10 to 50 kilometers. But future advancements in this field will undoubtedly allow more significant distances to be achieved. “Other work is investigating 'polar stationary orbits', termed 'pole-sitters' by Forward, which use continuous low thrust to allow a spacecraft to remain on the Earth's polar axis, high above the Arctic or Antarctic. These orbits could be used to provide new vantage points to view the Earth's polar regions for climate monitoring,” McInnes concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //