Investigators at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) say that they may have found a new way of blocking the growth of cancer tumors. The method relies on disabling a protein receptors that spreads the incorrect cellular signals which allow the cells to multiply out of control.

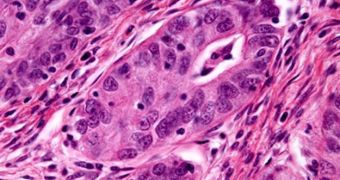

One of the hallmarks of tumors is the fact that cells making them up refuse to die when their time is due. They suffer mutations that disable the controlled cellular death mechanism which generally sends a kill signal once the cell has reached the end of its life.

When a cell divides a lot more than it should, the risk of harmful mutations grows in turn. At one point, tumors start developing, and all the cells within grow out of control, propagating their mutations.

The chemical signal that instructs the tumor cells to continue with their division is spread through several molecules, including the protein receptor HER3. Working together with experts at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), the MIT team found a way of shutting this protein down.

The molecule has a few “cousin” that are well-known for their role in cancer, including EGFR and HER2. Scientists who have developed chemical aimed at shutting the latter down say that their drugs are proving effective in trials.

In the future, treatments that use these drugs may be augmented with chemicals that fight HER3 as well. The molecule has been demonstrated to be involved in ovarian and pancreatic cancer, some of the most brutal forms of the disease.

Details of the new work appear in a paper published in the May 26 online issue of the esteemed medical Journal of Biological Chemistry, says MIT professor Linda Griffith, the co-leader of the study.

Cardiologist Richard Lee, who holds joint appointments at the BWH and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, was the other leader of the work. The two say that their findings were made by mistake, while they were working on a regenerative medicine program.

“It was not something we were expecting to see – you don’t expect to shut off a receptor with something that normally activates it – but in retrospect it seemed obvious to try this approach for HER3,” Griffith says.

She holds an appointment as the MIT Department of Biological Engineering School of Engineering professor of innovative teaching. The expert is also the director of the Center for Gynepathology Research.

“We pursued it only because we had people in the lab working with cancer cells, and we thought, ‘Since it had these effects in stem cells, let’s just try this in tumor cells, and see if something interesting happens’,” she concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //