Officials at the Gemini South Telescope, in Chile, announce that the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI) high-contrast imaging instrument has just been commissioned to active duty, after nearly 10 times of construction, development and testing. The GPI is capable of imaging extrasolar planets directly.

The Gemini Observatory is an installation comprising two 8.19-meter (26.9-foot) telescopes, located in Hawaii and Chile. It is one of the most advanced astronomical complexes for optical and infrared studies, and was developed by the United States, Canada, Chile, Brazil, Argentina, and Australia.

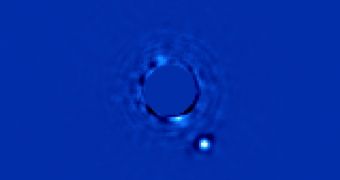

GPI is the world's most advanced exoplanet imager, capable to photographing alien worlds directly in orbit around their parent stars. Other telescopes can only detect exoplanets by the gravitational tug they exert on their parent stars. Additionally, the GPI can also probe the atmospheres of distant worlds.

Astronomers hope that the instrument will help them learn more about the dusty rings around newly-formed stars. These structures, called protoplanetary disks, are where new planets form via the clumping up of dust and other material around gravitational nuclei.

“Even these early first-light images are almost a factor of 10 better than the previous generation of instruments. In one minute, we are seeing planets that used to take us an hour to detect,” explained the leader of the team that built the instrument, US Department of Energy's (DOE) Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) investigator Bruce Macintosh.

The early first light GPI images, depicting a dust ring surrounding the very young star HR4796A, were released to the public during a presentation held at the 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), currently being held in Washington, DC.

According to the team, GPI collects data in infrared wavelengths, and specializes in studying young gas giants the size of Jupiter, which orbit their parent stars widely. The instrument was first pointed at the sky in November 2013, and scientists have been calibrating it ever since.

“Most planets that we know about to date are only known because of indirect methods that tell us a planet is there, a bit about its orbit and mass, but not much else,” Macintosh explained.

“With GPI we directly image planets around stars – it’s a bit like being able to dissect the system and really dive into the planet’s atmospheric makeup and characteristics,” he went on to say.

According to the GPI feature sheet, the instrument can see planets that are up to one million times fainter than their parent stars. This capability is essential for this type of investigations, since the brightness of a star usually makes that of their accompanying exoplanets fade away quickly.

During its trail run, the instrument imaged the well-known Beta Pictoris b exoplanet in the Beta Pictoris system, as well as the Jovian moon Europa, which is entirely encased in ice. Scientists with GPI say that the instrument may be used to track how the surface of the moon changes over time.

“GPI represents an amazing technical achievement for the international team of scientists who conceived, designed, and constructed the instrument, as well as a hallmark of the capabilities of the Gemini telescopes,” says Dr. Gary Schmidt.

“It is a highly-anticipated and well-deserved step into the limelight for the Observatory,” adds Schmidt, who holds an appointment as a program officer with the US National Science Foundation (NSF). The agency sponsored the US involvement in the Gemini Observatory partnership.

The international astronomical community could benefit tremendously from the activation of GPI. Until now, the most advanced method of identifying exoplanets was the transit technique that the NASA Kepler Space Telescope has used to detect more than 3,500 exoplanetary candidates over the past four years.

With the Gemini Planet Imager, exoplanets will be imaged directly, with experts gaining in-depth knowledge of their orbits and atmospheric properties at the same time.

“Seeing a planet close to a star after just one minute, was a thrill, and we saw this on only the first week after the instrument was put on the telescope! Imagine what it will be able to do once we tweak and completely tune its performance,” concludes GPI staff scientist Fredrik Rantakyro.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //