Whenever paleontologists and archaeologists find a complete skeleton of an extinct beast, or the fossilized remains of an entire dinosaur, they are able to reduce the large mystery surrounding these animals by a tiny fraction. But all these discoveries, all the digging and the effort amounts to very little, if researchers can't determine what these creatures looked like on the inside. For the very purpose of establishing their basic anatomic traits, experts have created a new field of research, namely computer-assisted paleontology, in which virtual models of dinosaurs are constructed, based on the archaeological finds, and then muscles are digitally added.

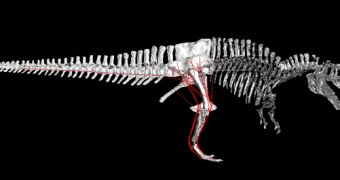

In this type of studies, the scientists want to determine what the actual configuration of the muscles may have looked like millions of years ago. They start off slowly, by intuitively attaching virtual muscles to the skeleton, but University of Manchester Computer Paleontologist Peter Falkingham says that such an approach inevitably results in the computer-generated animal falling on its face. Together with fellow researcher Bill Sellers, he has developed a new algorithm for figuring out how the muscles were attached to the body, one that functions in very much the same way as genes do.

That is to say, the algorithms themselves are able to “evolve” and to seek the best possible outcome for the face of the creature they are modeling. The researchers hope that, by using this new technique, they could potentially understand how, for example, Tyrannosaurus Rex had its muscles spread throughout its body, and in what sequence it activated them in order to walk and become an effective predator.

“Tracks can tell you so much that skeletons can't. They can tell you about the sot parts of the feet that weren't preserved over time. They can tell you how the animal moved, how it walked or ran. They can even tell you about the environment they lived in, and perhaps show you they may have moved considerable distances,” Falkingham told LiveScience.

Speaking about the difficulty of analyzing fossilized footprints, he added that, “Is the sediment made of tiny clay particles that stick together, or larger sand particles that roll over? What is the water content, which can help particles stick together, but if you put in too much, it pushes particles apart? What is the strength, elasticity and compressibility of the soil? And what happens when you have layers of sediment? The impressions left behind at lower layers can be very different from the ones left on the surface.”

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //