Bacteria and other microorganisms are known for their remarkable ability to become immune to nearly everything thrown at them, and now a new study provides us with some hints of how that's possible.

Short of being cast into the Sun, in Earth's inner core, or in the deepest corners of space, bacteria can endure anywhere you can think of.

They live happily in underwater frozen lakes, miles below the surface of Antarctica, or on the rim of volcanoes. Microbe colonies have also been found in the toxic environment around hydrothermal vents.

But bacteria can also endure in space, where they are battered by cold, vacuum and radiation, as evidenced by new studies conducted on the International Space Station (ISS).

Returning to Earth, the microorganisms prove to be extremely resilient to diseases, other infectious agents, and also to drugs we develop specifically to kill them.

Now, a team of investigators at the Rice University, in the United States, used tools belonging to computational biology to figure our how the bacteria develop and use this ability to adapt.

The influence that phenomena such as natural selection and evolution have on the entire process were also analyzed in fine detail, the team shows in the latest online issue of the esteemed scientific journal Physical Review Letters.

“From a purely scientific perspective, this research is teaching us things we couldn't have imagined just a few years ago, but there's an applied interest in this work as well,” explains scientist Michael Deem.

“It is believed, for instance, that the bacterial immune system uses a process akin to RNA interference to silence the disease genes it recognizes, and biotechnology companies may find it useful to develop this as a tool for silencing particular genes,” he goes on to say.

Deem is the John W. Cox Professor in Biochemical and Genetic Engineering at Rice, and also a professor of physics and astronomy at the university.

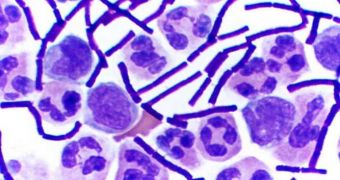

The work was largely focused on a section of bacterial genome that is known as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, or CRISPR for short.

According to Deem and graduate student Jiankui He, it may be that this portion of the genome plays a critical part in the bacteria's immune responses.

“Bacteria get attacked by viruses called phages, and the CRISPR contain genetic sequences from phages,” the team leader says.

“The CRISPR system is both inheritable and programmable, meaning that some sequences may be there when the organism is first created, and new ones may also be added when new phages attack the organism during its life cycle,” Cox adds.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //