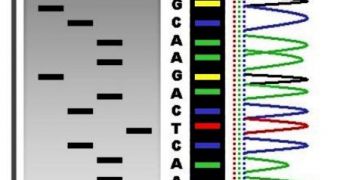

According to healthcare experts, the fact that genetic sequencing could be used to determine all there is to know about a certain disease is misleading sometimes, and a straight-up lie most of the times. They add that functional tests also play a critically-important part in figuring out what plagues a patient.

Understanding human disease is something that has eluded experts since the dawn of time. For all our modern technology, we have yet to figure out the conditions and triggers that make diseases appear.

But investigators at the Duke University Medical Center show in a new study that we may be hampering our own efforts to do so, if we only turn to sequencing for the answers. The team says that functional tests should be considered of more importance.

These tests are needed in order to get a clearer picture of what type of biological relevance the results of sequencing studies have in each patient's case. This is especially useful in ciliopathies, diseases that make the patient display numerous symptoms, usually associated with many conditions.

“Right now the paradigm is to sequence a number of patients and see what may be there in terms of variants. The key finding of this study says that this approach is important, but not sufficient,” explains study leader Nicholas Katsanis, PhD.

“If you really want to be able to penetrate, you must have a robust way to test the functional relevance of mutations you find in patients,” the investigator goes on to say, quoted by Science Blog.

“For a person at risk of type 2 diabetes, schizophrenia or atherosclerosis, getting their genome sequenced is not enough – you have to functionally interpret the data to get a sense of what might happen to the particular patient,” he adds.

Katsanis holds an appointment as the Jean and George Brumley Jr., MD, Professor of Pediatrics and Cell Biology at the university, and is also the Director of the Duke Center for Human Disease Modeling. He is a world expert in ciliopathies such as Bardet-Biedl Syndrome.

“This is the message to people doing medical genomics. We have to know the extent to which gene variants in question are detrimental – how do they affect individual cells or organs and what is the result on human development or disease?” explains Erica Davis, PhD.

She is the lead author of the new investigation, and works as an assistant professor in the Duke Department of Pediatrics. The expert also holds an appointment at the Duke Center for Human Disease Modeling.

“Every patient has his or her own set of genetic variants, and most of these will not be found at sufficient frequency in the general population so that anyone could make a clear medical statement about their case,” she concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //