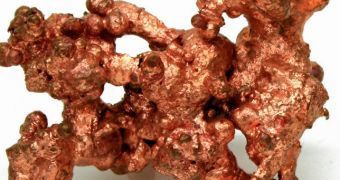

Scientists are currently constructing a new model to explain how the magnetic field generated by our planet looked and acted like during the Iron Age. This is done by analyzing artifacts produced by copper smelting during those days.

The primary conclusion that experts derived from the research was that Earth had a much stronger and more variable magnetic field during those days, a lot more so than experts previously calculated.

“This is a very challenging result. It’s completely outside of anything we thought could be happening in the core,” explains researcher and geomagnetist Luis Silva, who is based at the University of Leeds, in the United Kingdom. He did not participate in the new study.

The planet's core, and the changes it causes in the magnetic field, are interesting topics of analysis, that can bring about a better understanding of Earth as a whole. The field of science dealing with studying the history of the magnetic field is called paleomagnetism.

Paleomagnetists say that the planet usually varies its own magnetic fields gently, at a rate of about 16 percent every 100 years or so. However, the intensity variations discovered to have existed during the Iron Age cannot be readily explained.

The research showed a time when the field intensity double and then reverted to normal values within less than 20 years, which was thought to be impossible, Wired reports.

“The magnetic field reached an intensity that was much higher than anyone had ever thought before, two and a half times the present field,” explains scientist Ron Shaar.

“And you can have dramatic changes in the intensity of the field in periods of less than decades,” adds the scientist, a graduate student at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and also the lead author of a new study detailing the findings.

The researcher also presented the new results at a workshop held on December 14 in San Francisco, at the 2010 annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

Shaar said that the study will also be published in an upcoming issue of the esteemed journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters. He revealed that the samples for the study were taken from ancient Egyptian copper mine.

At this point, the scientist and his team are considering visiting some Roman mines as well, in order to collect additional copper samples, and determine whether the same readings can be derived from them as well.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //