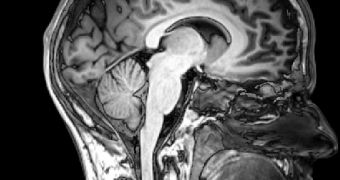

A team of medical researchers from the University of Utah – U of U, have managed to diagnose autism using a MRI scan, by analyzing the communication between the left and the right brain hemispheres.

This new step could help health care providers identify autism much earlier in children, and also lead to a better treatment for those who already have the disorder.

The researchers were led by neuroradiologist Jeffery S. Anderson, MD, PhD, U of U assistant professor of radiology, and identified areas within both hemispheres of autistic people, that do not communicate correctly with one another, by using MRI.

These brain areas are called 'hot spots' as they are responsible for motor skills, attention, face recognition and social behavior – all these elements being abnormal in autism, and on the MRIs of people without this disorder, there are no such deficits.

Anderson said that “we know the two hemispheres must work together for many brain functions, [so] we used MRI to look at the strength of these connections from one side to the other in autism patients.”

The study focused on nearly 80 autism patients, aged 10 to 35 years old, and lasted for a year and a half before completion.

These results will be added to an existing autism study which follows 100 patients over time.

Lainhart said that “the longitudinal imaging data and associated knowledge gathered forms a unique resource that doesn't exist anywhere else in the world.”

The only major structural difference between the brains of healthy people and those suffering from autism is the increased size of the brains of young children with autism, being about the only thing that can be seen in a routine brain MRI scan.

The new study proves that if studying the communication between regions of the brain, more differences can be identified.

Along with other research going on at U of U, involving the use of diffusion tensor imaging – measuring the microstructure of white matter connecting brain regions, scientists are gathering important data on autism.

We now know that MRI is a potential tool for diagnosing the disability, so patients could be screen objectively, rapidly and early on, making interventions more successful.

Janet Lainhart, MD, U of U associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics and the study's principal investigator, said that “we still don't know precisely what's going on in the brain in autism.

“This work adds an important piece of information to the autism puzzle, [because] it adds evidence of functional impairment in brain connectivity in autism and brings us a step closer to a better understanding of this disorder.

“When you understand it at a biological level, you can envision how the disorder develops, what are the factors that cause it, and how can we change it.”

As science and technology evolve, researchers hope that one day they will be able to use data from the MRI to biologically identify several types of autism.

“This is a complex disorder that doesn't just fall into one category,” Lainhart says.

“We hope the information can lead us to characterizing different types of autism that may have different symptoms or prognoses that will allow us to identify the best treatment for each affected individual.”

The team of scientists uses research from the departments of psychiatry, radiology, and pediatrics, the Neurosciences Program, the Scientific Computing and Imaging Institute, and The Brain Institute at the U of U, as well as collaborators at Brigham Young University, the University of Wisconsin, and Harvard University.

The study will be published on October 15, 2010 in Cerebral Cortex online.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //