The best biological weapon is based on a bacterium against which there is no vaccine, and sadly, the next 'World War' could be one of bioweapons, so scientists are working relentlessly on developing a vaccine against plague.

After the terrorist attacks of 9/11, an anthrax scare made bioterrorism a real threat, so the federal government began funding vaccine research against threats of the sort.

Stephen Smiley, a leading plague researcher and Trudeau Institute faculty member, said that “governments remain concerned that bioweapons of aerosolized Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that causes plague, could kill thousands.”

Dr Smiley said that there is no licensed plague vaccine in the United States, so along with postdoctoral associate Jr-Shiuan Lin, he is working on developing a vaccine that will protect the public and the armed services from what he calls a 'plague bomb'.

Even though this research focuses on tackling plague used as a bioweapon, around the world there are still small, natural outbreaks of the disease to this day, so if the researchers succeed, the plague vaccine will protect against both natural and manufactured outbreaks.

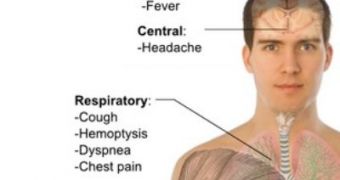

Yersinia pestis is the most deadly bacteria known to man, and plague infections of the lung (pneumonic plague, with bacteria growing both inside and outside the cells of the lungs) are highly lethal, leading to death within a week of infection.

The majority of plague vaccine candidates, stimulate B cells to produce plague-fighting antibodies, but animal studies suggest that antibodies are not enough to protect humans from the disease.

So, Smiley laboratory tried another approach, and showed that T cells can also fight plague.

The team had already proven that a single immunization with an experimental vaccine increases the production of T cells and provides partial protection against pneumonic plague, and now, new data shows that a second immunization boosts the protection that T cells provide.

Dr Smiley said that “it is particularly exciting that the boost seems to improve protection by increasing a newly described type of T cell, which we call a Th1-17 cell.”

This cell is a mix of the two T cells, and it has both their characteristics – Th1 cells defend against intracellular bacteria and Th17 cells are experts at killing extracellular threats.

Also, Dr Smiley thinks that these new Th1-17 cells could be effective in fighting other types of pneumonia too.

“Bacterial pneumonia is one of the most common causes of death in hospitals and, like plague, many of these pneumonias are caused by bacteria that grow both inside and outside the cells of our bodies,” he said.

These studies are funded by the Trudeau Institute and grants from the National Institutes of Health, the research being supported by government grants and philanthropic contributions.

The findings are reported in the current issue of The Journal of Immunology.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //