In the case of many species, individuals have an innate sense of direction, following their way along migration routes that go by thousands of miles and in most of those species, Earth's magnetic field is used for orientation or navigation during long migrations. This is valid for more living creatures: from bees to sharks, sea turtles, bats, dolphins and whales.

40 years ago Wolfgang Wiltschko of Frankfurt University had been the first to reveal that European robins rely on the Earth's magnetic field to navigate during their seasonal migrations. Since then a similar magnetic ability has been discovered in over 20 bird species, songbirds and pigeons and in the bobolink and domestic doves magnetite crystals were even encountered in their beaks. But now, Wiltschko's team has discovered that domestic chickens, too, are equipped with magnetic sensors. The research team trained newly hatched chicks of domestic chickens to take a red ball as their "mother".

At each corner of the chicks' pen, the researchers placed a white screen. The chicks learned to find the "mother" red-ball always behind the magnetic North corner.

"They tend to head into the direction where they were trained to find their 'mother,'" Wiltschko told LiveScience.

When the researchers shifted the magnetic field so that magnetic North was in the geographic East direction and let the chicks go in the pen, "they shifted their search activity accordingly, demonstrating that they relied on the magnetic field," Wiltschko said.

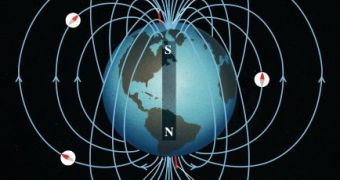

Other test revealed that, like European robins, chicks can detect a so-called inclination (the angle) of the magnetic-field lines to the surface of the Earth. They can distinguish between pole-wards, where the lines dip downward, and equator-wards, where the lines tilt upward.

"The magnetic sensors are probably located in the chicks' eyes, where its photoreceptors detect light," Wiltschko said. This is based on an experiment which revealed that the birds could orient themselves under blue light but totally lost the sense of direction under longer-wavelength lighting.

The order of the chickens (Galliformes) and that of the robins (Passeriformes) split from a common group over 66 million years ago. As both groups possess a similar magnetic compass, this means birds developed this ability early in their evolution, much before the migration behavior emerged.

"This suggests that the avian magnetic compass may have evolved in the common ancestor of all present-day birds to facilitate orientation within the home range," wrote the researchers.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //