In a new investigation, scientists have discovered that a type of brain signal is active in the sleeping brain even when it should not be. Alpha waves are usually associated with staying awake, and researchers believe that their presence in the sleeping brain may in fact be hindering sleep.

The fact that alpha waves still remain active when a person closes their eyes is well known. If someone is relaxed, but with eyes closed, then alpha wave activity diminishes, but does not disappear.

However, it was commonly believed among scientists that these waves – which originate in the back of the head – stopped propagating once the person entered a deep sleep. This turned out not to be the case.

In the investigation, scientists were able to determine that the alpha waves merely went undercover in the sleeping brain, but that they were still there. Analyzing them live may help scientists in sleep research centers determine how deep people are actually sleeping.

This could also help determine precisely what amount of noise is needed to wake a sleeper up. Details of the investigation and its applications appear in the March 3 issue of the peer-reviewed journal PLoS ONE, which is published by the Public Library of Science.

According to University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia sleep researcher Mathias Basner, who was not a part of the investigation, the new discoveries indicate that, in reality, sleeping is a dynamic process.

In other words, it would seem the brain activity levels and patterns change constantly during sleep, and not only between the defined stages of sleep researchers discovered thus far, Science News reports.

“It may suggest that something is going on in the central nervous system that we don’t know about and should maybe pay more attention to,” Basner goes on to say.

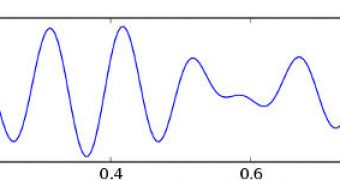

Scott McKinney, the coauthor of the research paper, says that no one purposefully ignored alpha waves. The omission is due to the fact that experts use electroencephalographs (EEG) to measure brain activity.

The diagrams these devices produce are hard to interpret with the naked eye. This is why McKinney, who is based at the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Harvard University, used computer programs to break them down into their individual components.

Investigators discovered that the alpha waves are simply drowned by more powerful brain signals, but that they were still active nonetheless.

“The classical way we’re scoring sleep may not give a good handle on what a patient really experiences. This new way of analyzing depth of sleep may be used to get a better understanding of a patient’s complaint,” explains Phyllis Zee.

She is the director of the Sleep Disorders Program at Northwestern University in Chicago.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //