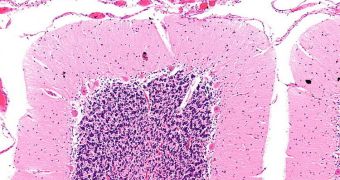

In a groundbreaking new discovery, researchers at the University of Royal Holloway in London, the United Kingdom, found out that the cerebellum plays an important role in the storage of memories required for important mental skills.

Such skills include for example driving. The general rules of the road, once assimilated, are processed unconsciously every time a person drives, but they are stored in the cerebellum too, experts say.

Modern neuroimaging techniques are allowing investigators to look deeper and deeper into the human brain, and learn how it operates. The pathways memories take when they develop are beginning to be discovered, and the flow of information understood.

Determining the exact mechanisms the human brain uses to learn and memorize things would be a discovery of monumental proportions, as it would literally mean that we could become capable of making our selves better data-storage systems.

Having the ability to remember as many things as possible would be invaluable, and could help our society as a whole. But, before this objective is reached, experts need to make sense of how information travels through various brain regions and pathways.

The UK research team left from an established truth, and namely that practice and skill make certain moves automatic. This means that the brain simply doesn't pay any attention when it performs them.

Riding a bicycle or catching a ball are good examples of such actions. When performing them, the brain takes some time off, to avoid getting you painfully bored. The same holds true for commuters taking the same route every single day.

The new investigation demonstrates that the cerebellum is involved in implementing memories of this actions into the conscious attention. This in turn allows the prefrontal cortex – one of the newest areas of the brain in evolutionary terms – to remain free for solving other problems.

Details of the new investigation were published in the latest issue of the esteemed scientific Journal of Neuroscience, PsychCentral reports.

“The study adds to the groundwork for understanding cognitive deficits in patients with cerebellar damage and improving strategies for their rehabilitation,” says URH researcher Narender Ramnani, PhD.

“It also raises the possibility that the cerebellum might be used for the skillful, automatic and unconscious use of mathematical and grammatical rules,” the expert concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //