The NASA Cassini spacecraft has recently carried out a flyby of the small Saturnine moon Methone, as it was positioning itself for its last pass over the large moon Titan. The orbiter is currently getting ready to shift from an equatorial to a polar orbit, which will enable it to observe Saturn's poles in detail.

This change implies that the vehicle will not be able to carry out flybys of the most interesting moons orbiting the gas giant for about three years. After the upcoming Titan pass, it will no longer meet this moon, or Enceladus, until 2015.

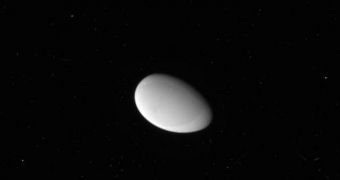

Cassini has observed Methone only once before, on June 8, 2005, from a distance of about 225,000 kilometers (140,000 miles). Since the moon is only 3 kilometers (2 miles) wide, the spacecraft could not make out the object in much detail.

The new flyby, which occurred on Sunday, May 20, took Cassini very close to the moon, at a distance of just 1,900 kilometers (1,200 miles). This enabled it to observe some of the landscape features on the surface of Methone.

The same day, the NASA spacecraft also imaged Tethys, a 1,062-kilometers (660-mile) wide moon of Saturn. Cassini passed within 54,000 kilometers (34,000 miles) of the object, and is scheduled to rendezvous with Titan today, May 22.

This flight will take the orbiter very close to the surface of Saturn's largest moon, at an altitude of just 955 kilometers (593 miles). The gravitational influence of the object will put Cassini on a 16-degree tilt from the gas giant's equatorial plane.

According to mission controllers at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in Pasadena, California, the spacecraft does not have thrusters capable of placing it in such inclined orbits. However, careful trajectory planning can take advantage of the gravitational influences exerted by several moons.

Over the next few months, Cassini will carry out a series of flybys that will eventually set it on a 62-degree tilt from Saturn's equatorial plane, where the planet's rings and most of its moons are located. The last time the orbiter flew such inclined orbits was in 2008, when it reached a 74-degree tilt.

“Getting Cassini into these inclined orbits is going to require the same level of navigation accuracy that the team has delivered in the past, because each of these Titan flybys has to stay right on the money,” JPL Cassini Program Manager, Robert Mitchell, explains.

“However, with nearly eight years of experience to rely on, there's no doubt about their ability to pull this off,” the official goes on to say.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //