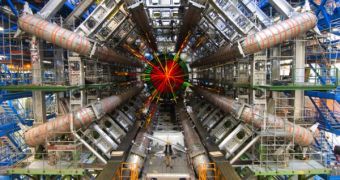

The Large Hadron Collider at CERN, is used to get an insight on the origins of the Universe and thanks to Dr Andreas Warburton of McGill’s Department of Physics, the first results from the analysis made at the LHC have been published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Researchers working at the LHC were trying to recreate a miniature version of the event that originated our Universe, and they used Einstein’s e=mc2 equation to do so.

The experiment is known as “ATLAS”, and it is studying the head-on collisions of protons of very high energy, in an attempt to find out more about the forces that have formed the Universe.

Canadian scientists can be proud of their co-national, as Dr Andreas Warburton of McGill’s Department of Physics has made leading contributions to the analysis of data from this experiment.

Along with his 3171 colleagues from all around the world, Dr Warburton looked for new particles, whose existence has been suggested by theoretical calculations.

He explained that “understanding whether new kinds of matter exist or not is interesting because it holds clues to knowledge about how the Universe works fundamentally.

“The Standard Model of Particle Physics is a useful theoretical framework but it is known to be flawed and incomplete – we are searching for new particles that lie outside this framework, and we are also seeking to establish the non-existence of these hypothetical particles.”

This newly published research belongs to the second category and is about finding the mass of a theoretical particle called an “excited quark.”

In an attempt to explain the work being done at the LHC, Warburton said: “by exploring the high-energy subatomic frontier, it is metaphorically somewhat like turning over stones at the seashore and looking for new and interesting surprises hiding under the rocks.

“Here we are looking under stones that have been too heavy to lift before this summer, [and] what we see or don't see under those stones helps to paint new pictures about how the Universe works and tells us which stones are most important to look under next.”

“The results reported in our paper have been awaited for a long time and by many people,” Warburton added.

“There was friendly competition amongst us as to who will be the first to make a publishable measurement that either excludes or discovers New Physics, and I am proud that the ATLAS team won this race.

“I feel fortunate and privileged to have played a leading role in getting the analysis into a publishable form in a very short time.”

Warburton has since regained his office at McGill University.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //