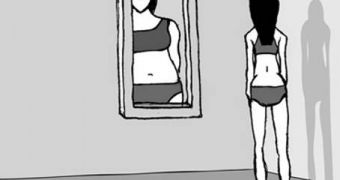

Scientists at the Heidelberg University Hospital have recently announced that they have discovered a series of brain mechanisms that makes it difficult for women suffering from anorexia to quit their destructive habit, and return to living a normal life. Usually characterized as a psychiatric illness in which sufferers have poor image perception of their own bodies and distorted eating habits, anorexia nervosa is very dangerous, and can lead to death in some instances. The new research sheds some light on the causes of this terrible disease.

According to medical statistics, more than ten percent of diagnosed anorexia nervosa patients die of the disease worldwide. In 20 to 30 percent of the cases, the illness goes chronic. Treating it is very difficult, doctors say, especially if the patient has been brought in late in the developmental stages of the condition. The situation is made worse by the fact that a large percentage of women, and even teenage girls around the globe voluntarily start depriving themselves of food, in an attempt to fit society's rigorous and essentially misplaced beauty standards. Slipping into anorexia is fairly easy thereon.

In the paper, conducted by scientists from the HUH Department of Psychosomatic and General Internal Medicine and the Heidelberg University Hospitals of General Psychiatry and Neurology, the researchers used a functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) machine to analyze the brains of some 30 anorexia patients and healthy young women. The instrument analyzes blood flows to certain regions of the brain, which indicate a larger or smaller degree of activity at those locations.

“In this study, we confirmed that anorexic patients cling to familiar behavioral responses more frequently than healthy subjects, thus suppressing alternative behavior,” the Head of the working group for eating disorder at the Hospital, Dr. Hans-Christoph Friederich, says. The fMRI scans also revealed that a neural pathway linking the cortex with the diencephalon was also less activated in the case of anorexia patients. This area of the brain plays an important part in initiating and controlling actions under rapidly changing environmental demands.

“We have developed a treatment program for anorexia patients that specifically targets the flexible modification of behavioral responses,” Dr. Friederich adds. Details of the team's finds are published in the June issue of the renowned American Journal of Psychiatry.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //