One of the most active areas in medical research at this point is the development of brain computer interfaces (BCI) that would allow patients to control a cursor on a computer screen, or an automated wheelchair with a robotic arm. Sensors hooked directly on the cortex pick up neural signals, which are then picked up by a computer, processed, and transformed into an action or set of actions that electronic devices can understand. Now, a new study seems to indicate that doing this may also benefit the brain.

Researchers write in the latest issue of the respected journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) that computers and brains apparently have the ability to influence each other as they interface. This means that, while the mind is used to move cursors on computer screens, or to manipulate wheelchairs, the brain is also receiving some training, the group believes. It was demonstrated in the investigation that the signals the brain produces for controlling BCI are stronger than those produced for the same task in real-life, hinting at an adaptive mechanism.

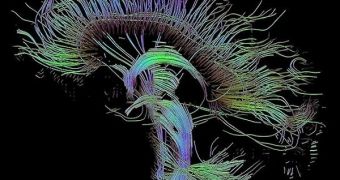

“Bodybuilders get muscles that are larger than normal by lifting weights. We get brain activity that's larger than normal by interacting with brain-computer interfaces. By using these interfaces, patients create super-active populations of brain cells,” explains University of Washington doctoral student in physics, neuroscience and medicine Kai Miller. The expert is also the lead author of the study. Moving beyond the amazing capabilities of the human brain, the finding suggests that the cortex may be extremely apt at detecting external devices, including robotic arms and other prosthetics. The researchers say that, in time, any new device controlled by neurons will become more integrated.

In a study on volunteers, the team determined that participants only required 10 minutes to adapt to the new system. They were asked to move a cursor on a computer screen, at first by imagining moving something inside their minds, so as to generate the necessary neural activity. After a bit of training, the test subjects reported being able to move the cursor via a BCI directly, without imagining that they were moving something else with their mind.

“The ability of subjects to change the signal with feedback was much stronger than we had hoped for. This is likely to have implications for future prosthetic work,” says UW professor of neurological surgery Dr. Jeffrey Ojemann, also a co-author of the new investigation. The research was funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), NASA's graduate student research program and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences' medical scientist training program.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //