When contemplating the idea of music, it immediately becomes obvious that blindness, or other types of visual impairments, are not an intrinsic barrier to achieve a high level of knowledge. Unfortunately, music sheets are pretty off-limits for blind musicians, since not many works of art have been translated in the Braille tactile language, which they can understand. It is estimates that only around 15 percent of all music sheets were transposed in the language, and also that the vast majority of these translations is only available at a local level. A new European project plans to change all that, AlphaGalileo reports.

By the first quarter of the 19th century, there was no way for would-be, blind musicians to learn the trade except by ear. This is not a problem for people who are not tone-deaf, but figuring out the notes of a classical piece by Chopin was, and is to this day, fairly difficult. Louis Braille changed all that when he created what is now the universally accepted language of blind and visually impaired people. In addition to providing a method for these individuals to read and write, the Braille language was also adapted to music, offering sighted musicians a way of translating their music sheets for their blind peers as well.

It is the stated goal of the CONTRAPUNCTUS Project to produce a rich, standardized digital format, to be used for the transcription of any music piece into Braille musical language. This would have the double effect of making the music sheets more complex and easy to read, and also more widely available to regions of the world where people don't enjoy this privilege today. The library can be accessed, browsed, and then musicians can download their favorite musical score. The database is continuously expanding, and the musicians themselves can add their own music sheets to it.

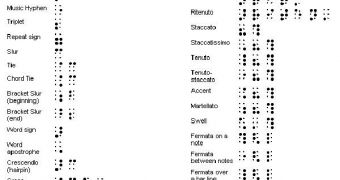

“The music page in Braille has been like a city with lots of blank walls and very few signs. CONTRAPUNCTUS has enriched this page with all kinds of information concerning every musical element – a note, a rest, a tie, fingering, etc. It used to be a labyrinth where you could go in but might never come out. Now, with our system, you can always find your way around,” project coordinator Antonio Quatraro explains. Scores are processed using a piece of software called RESONARE, and the end-result is a format called Braille Music Markup Language, or BMML. It can be played using an MIDI interface, the researchers add.

“As you read through the music on your computer, the notes are played to you as written. That’s important, since a commercial recording cannot be as accurate as the printed score, just as a spoken story cannot convey its spelling and punctuation,” Quatraro adds. “It’s as if you had driven all your life on a bicycle, and now you have a car,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //