Experts at the University College London (UCL), in the United Kingdom were following a recent study able to conclude that brain waves have a significant influence on human behavior. In a series of tests, they attached a number of electrodes on volunteers' heads, and then ran a small alternating current through them. In a paper detailing the experiments, published in the latest issue of the journal Cell Biology, the team reveals that such research could unlock new avenues of research for curing movement disorders, such as Parkinson's.

In such diseases, patients have a difficult time making voluntary movements, but the British team says that they managed to generate normal brain activity patterns in test subjects. “We induced the same patterns as you see in normal brains via electrodes,” explains UCL professor Peter Brown, who was also the lead author of the journal entry. His work was focused on learning how to boost the activity of a specific type of brain wave, called the beta oscillation, the BBC News informs.

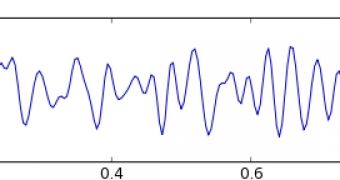

“Different parts of the brain work together and generate certain frequencies, and the movement areas of the brain come together in beta activity. That activity is suppressed just prior to and during movement, so we think the body gets rid of it to prepare to make a new movement,” the expert adds. Brain waves are generated by large numbers of neurons firing at the same time. In the case of beta waves, an irregular pattern indicates an active brain, while a constant one is an indicator of an outside influence, such as a drug.

“The currents we use are very small, but [they] shape the likelihood of neurons firing in the imposed rhythm,” Brown says. In the experiments, the participants were shown a dot on the screen, and were asked to move a joystick-controller marker to the dot's location as fast as they could, upon hearing a signal play. “When we applied the beta stimulation that quick movement was slowed by 10%. So we have a direct experiment showing a causal link between the oscillations and the behavior,” the scientist says. “This information is very helpful. Since we've shown that this slows people down, it tells us what Parkinson's disease treatments should be trying to suppress,” he adds.

“The theory is that […] in Parkinson's disease when people try to move they cannot suppress beta [brain waves] and therefore cannot move. This study is the first to show in normal subjects that beta activity actually slows movement. This supports a causal role for [the] activity in causing a fixed posture and tending to prevent voluntary movements,” Brown concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //