A blood test that can reliably detect gene doping even after 56 days, was developed by German scientists from Tübingen and Mainz.

Until now it was impossible to prove that athletes had undergone gene doping, but the new method discovered by Professor Perikles Simon, MD, PhD from Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz and gene therapist Professor Michael Bitzer, MD from the University Hospital of the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Germany.

Professor Simon said the “for the first time, a direct method is now available that uses conventional blood samples to detect doping via gene transfer and is still effective if the actual doping took place up to 56 days before.

Unlike what was previously thought, there is no need to use “gene transfer via an extremely expensive indirect test procedure from molecular medicine”, to detect gene doping, says professor Bitzer.

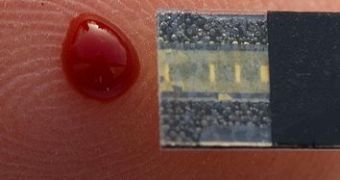

This new method “represents a relatively low-cost method of detecting several of the most common doping genes,” says Simon, in the presentation of the process.

“The process of inserting individual genes in specific body cells stems from the idea of curing severe illnesses with this new technology,” he adds.

The key to determining whether or not there was gene doping is transgenic DNA, or tDNA.

Four years ago, when Simon was a member of the University Hospital in Tübingen, he developed a procedure that helps detect even the smallest traces of transgenic DNA in the blood.

The transgenic DNA gets inside the body through viruses and creates performance-enhancing substances like erythropoetin (EPO) that form red blood cells.

Simon explains that because of the tDNA, the body of a gene-doped athlete makes its own performance-enhancing hormones, as “over time, the body becomes its own doping supplier.”

The efficiency of the procedure he has developed, has now been proven for the first time in lab mice.

The very reliable and sensitive detection method was verified on 327 blood samples taken from professional and amateur athletes.

What scientists managed to do was to insert the foreign genetic material extremely only in the muscles around a small puncture area.

Two months after the genes were injected into the muscles, there were still differences between the gene-doped mice and the others.

In the next few months, the University Hospital in Tübingen is planning a therapy study for advanced tumor patients.

The researchers now hope that athletes will be stimulated to no longer use gene therapy for doping purposes.

This research was financed by the World Anti Doping Agency (WADA), with a total of $980,000 over a four-year period, and the results were published in the online edition of the journal Gene Therapy.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //