Experts have been wondering for a very long time about how bacteria can produce species-specific wavelengths from their cells, without the presence of any discernible, specialized apparatus. A new study suggests that their chromosomes may play a role in underlying this ability.

According to the conclusions of a new study, the structures basically act like antenna, enabling electrons to travel through a variety of gene circuits, but in a very specific manner. This is only one of the theories proposed to explain how bacteria can generate electromagnetic signals.

This new proposal comes from a team led by Northeastern University theoretical physicist Allan Widom. While biologists still debate whether bacteria can indeed produce such signals or not, the expert says that it's theoretically possible for the phenomenon to exist inside these microorganisms.

His calculations included the known properties of DNA and electrons. Widom says that he couldn't find any theoretical reason for why bacteria couldn't produce these signals, Wired reports.

“For a long time, there have been signals in water. Something is happening around a kilohertz. You have to look for natural energy levels in the system that would give you a kilohertz frequency,” explains Widom.

“With the lengths of DNA and the mass of the electron, you get the right frequency range for these signals,” adds the expert, who is also the lead author of a new paper detailing the findings.

The work was published in the April 15 issue of the journal arXiv. It builds on research published in 2009 by Luc Montagnier, a French virologist who was the first to propose that bacteria are capable of radio transmissions.

Montagnier, who won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Medicine for linking HIV to the development of AIDS, had his work met with a lot of skepticism. He also proposed that the radio signals were causing loose pieces of DNA in a test liquid to assemble into bacteria-like structures.

After publishing these findings, he moved to the Jiaotong University in Shanghai. In response to the critics he was subjected to from peers, he said that European scientists are intellectually fearful to conduct investigations in this line of research.

“It’s not pseudoscience. It’s not quackery. These are real phenomena which deserve further study,” Montagnier explained before leaving France.

In his work, Widom agrees that bacteria such as Escherichia coli are theoretically capable of producing electromagnetic emissions in the potion of the spectrum that Montagnier said it discovered radio signals.

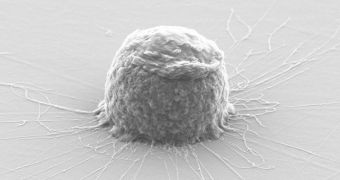

“Different species have different lengths of DNA [inside chromosomes]. These lengths probably determine frequency,” the Northeastern University expert adds. He adds that studies conducted in recent years have revealed the existence of bacteria that communicate through nanowire-like structures.

“This could be a wireless version. Bacteria that set up nanowires are, on an evolutionary scale, fairly old. It’s occurred to me that more modern bacteria may use wireless,” Widom argues.

The expert proposes that cells in higher lifeforms, including humans, could also be using this form of communications to stay in touch with each other. However, he says that he will not investigate the matter further, since this is not his area of expertise.

According to experts, we may be on the brink of a major scientific discovery. All that is needed is for research teams to start investigating this issue in depth, rather than dismissing it right off the bat.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //