Consider the following situation in which an oil tanker capsizes and spills thousands of gallons of crude into the sea. This is the recipe for ecological disaster by any book, and scientists have been working on devising a way of mitigating the effects of such an accident ever since the Exxon Valdez incident. Now, with the help of a certain type of bacteria, they believe they may have made environmental cleanup easier and more effective. The microorganisms could also be used to generate fuel and to produce new classes of organically made materials, Science Now reports.

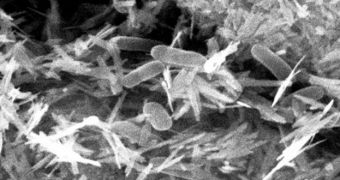

The rock-dwelling bacterium called Shewanella has been found to be able to morph the minerals it comes in contact with by zapping them with small electrical shocks that it generates itself. The good news is that the microorganism is relatively common, which means that, if it is employed in cleanup systems or in new, advanced fuel cells, it could be made readily available on demand.

Investigations into how anaerobic bacteria – that live without consuming oxygen as we do – have been ongoing for more than 50 years. Scientists have been trying to determine the molecular mechanisms that the creatures use to extract electrons from sheer rock, without having to break apart oxygen in the atmosphere for the job. Now, a joint team, made of experts from the United States and the United Kingdom, believes it may have found the answer to these questions. It took it more than five years to finalize its work, it reports.

Shewanella is apparently able to employ the help of a specific class of proteins that reside on its surface, which in effect act like electrical wires, connecting the inside of the bacteria to the outside world. These proteins bind with molecules in the rock, and convey electrons towards the outside structures through the cellular membranes. These membranes are usually insulators, but they can allow for the electron flow to pass. When this happens, the chemical structure of the rock is altered, and elements such as iron and manganese are produced.

Pennsylvania State University expert Susan Brantley adds, “As a geochemist, I was surprised to see just how much 'machinery' the microbe builds to move electrons.” She is also a coauthor of a new scientific paper detailing the findings, which appears in this week's online issue of the respected journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Shewanella and related bacteria could be used in electricity production and oil-spill cleanup on account of their properties, she and her colleagues explain in the paper.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //